Exoplanets are a fascinating aspect of the study of the Universe.

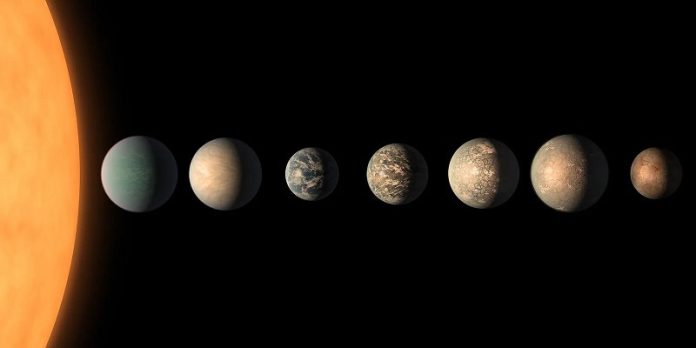

TRAPPIST-1 is perhaps one of the most intriguing exoplanet systems discovered to date with no less than 7 Earth-sized worlds.

They orbit a red dwarf star which can unfortunately be a little feisty, hurling catastrophic flares out into space.

These flares could easily strip atmospheres away from the alien worlds rendering them uninhabitable.

A new piece of research suggests this may not be true and that the rocky planets may be able to maintain a stable atmosphere after all.

Exoplanets are alien worlds outside of our solar system orbiting other stars. Their discovery in the 1990’s was just the beginning and to date over 5,000 have been identified.

They vary massively in composition from small, rocky Earth-sized planets to gas giants like Jupiter.

A few of them orbit in the host star’s habitable zone raising the tantalising possibility that life may exist out there in the universe.

All manner of techniques and telescopes have been used to hunt for exoplanets and to explore their nature.

More recently the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) which was launched in late 2021 has been engaged to that end. The design of the JWST is such that it is capable of observing nearby exoplanets in greater detail than before.

TRAPPIST-1 is 40 light years away in the constellation Aquarius. It is one of the most fascinating exoplanetary systems discovered to date with 7 Earth-sized planets in orbit around a cool dwarf star.

Like all stars, TRAPPIST-1 has a habitable zone, a region around the star within which, the conditions are likely to be conducive to life for any planet that happens to be orbiting at that distance.

TRAPPIST-1 has 3 of the 7 planets orbiting in this zone offering a tantalising possibility of extra-terrestrial life.

The planets of TRAPPIST-1 are classic rocky objects in orbit around an M-dwarf star.

These stars are the most common in the universe but previous studies suggest the intense UV radiation from TRAPPIST-1 would fry any atmosphere or surface water.

It has been thought that the hydrogen molecules would escape, leaving behind significant quantities of reactive oxygen which would likely inhibit the development of organic chemistry.

A recent study led by the University of Washington has been published in the journal Nature Communications which suggests an alternative theory.

The team led by Joshua Krissansen-Totton suggest that instead, a stable atmosphere can be created and sustained following an alternative sequence of events.

During the evolution of the planet, and following its molten state, millions of years of cooling lead to the solid rocky planets we see today.

They report that their data shows hydrogen and other light gasses escaped out into space for planets near to the star.

For those that are further away where things are a little cooler, the hydrogen reacted with oxygen and iron deep inside the planet producing water and other heavier gasses. These processes may have created a stable atmosphere after all.

Observations from the JWST can detect higher levels of thermal infrared energy from the inner planets and they reveal the absence of a thick atmosphere.

The team suggest more distant planets may have a more stable environment that might even produce a habitable environment.

JWST has to date, been unable to detect atmospheres but with new ground based telescopes coming online and with new imaging techniques, the TRAPPIST-1 planets in the habitable zone may soon reveal their mysteries.

Written by Mark Thompson/Universe Today.