A new study has shed light on the mysterious craters that have appeared in Siberia’s permafrost over the past decade.

These craters, first discovered in 2014 on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, were caused by explosive releases of methane gas—a process driven by climate change, according to researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Spanish National Research Council.

The findings, published in Geophysical Research Letters, offer a fresh understanding of how warming temperatures can lead to these dramatic events.

The Yamal Peninsula, a remote, low-lying region in north-central Russia, gained attention in 2014 when a massive crater—about 70 meters (230 feet) wide—suddenly appeared in the permafrost.

Over the years, more craters were found in the area, sparking various theories about their origins. Some believed the explosions were caused by the buildup of methane gas due to permafrost melt, while others pointed to the proximity of natural gas reserves.

However, the new study found that permafrost warming alone wasn’t enough to trigger these explosions.

The research team discovered that a combination of the region’s unique geological features and climate change-induced warming was responsible. As the surface warms, it creates rapid pressure changes deep underground, leading to the release of explosive methane gas.

The researchers approached the problem by first asking whether the explosions were caused by physical or chemical processes.

They quickly ruled out chemical reactions and focused on physical causes. The answer, they found, lies in a process called osmosis.

Osmosis is a natural process where fluid moves to balance the concentration of dissolved substances on either side of a barrier. In the case of the Yamal Peninsula, the thick, clay-like permafrost acts as an osmotic barrier.

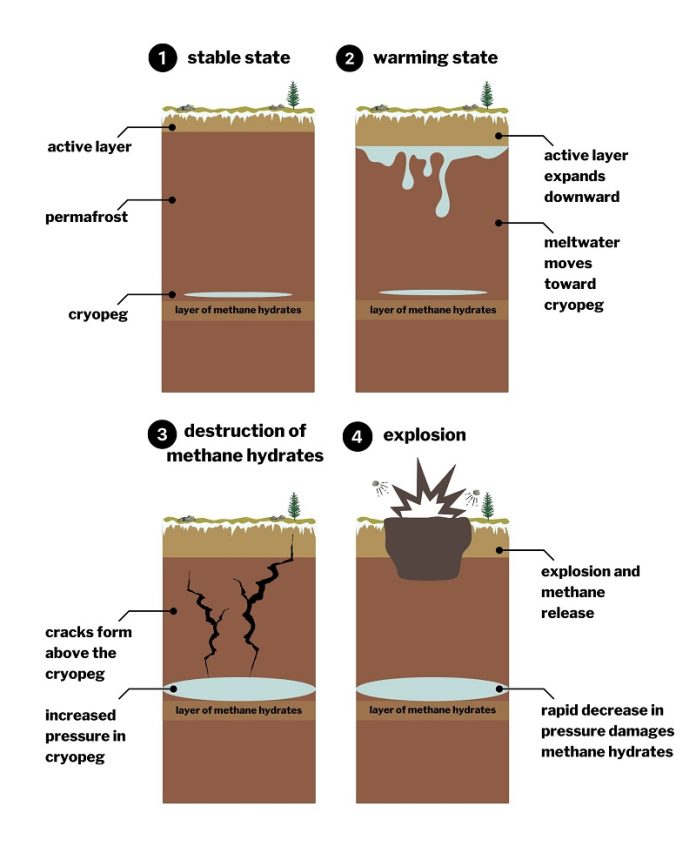

This permafrost layer, which is up to 980 feet thick, stays frozen year-round, with a thinner “active layer” on top that thaws and refreezes with the seasons.

Beneath the permafrost are layers of salty, unfrozen water called cryopegs, and below these, methane hydrates—a solid mixture of methane and water. Normally, these methane hydrates are stable, but as the climate warms, the active layer melts and sends water into the cryopeg through osmosis, increasing pressure.

This extra water creates a buildup of pressure in the cryopeg, eventually causing cracks in the soil above it. As these cracks form, the pressure at depth suddenly drops, destabilizing the methane hydrates and leading to an explosive release of methane gas.

The buildup leading to these explosions can take decades, and this timeline aligns with the increasing climate warming observed since the 1980s. While this phenomenon may be rare, the amount of methane released during these explosions could significantly contribute to global warming.

“This might be a very infrequent occurrence,” said Ana Morgado, one of the study’s authors. “But the amount of methane that’s being released could have a big impact on global warming.”

The study’s findings highlight the complex ways in which climate change and geological features interact, potentially leading to unexpected and dramatic events like the Siberian permafrost craters.