As the world shifts toward cleaner energy sources, the demand for rare earth elements (REEs) is rising rapidly.

These metals are essential for producing green technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines.

While REEs aren’t truly rare, large deposits are mostly found in a few places, especially in China, and they are difficult to extract.

Brendan Bishop, a Ph.D. student at the University of Regina, is studying new ways to source these valuable elements.

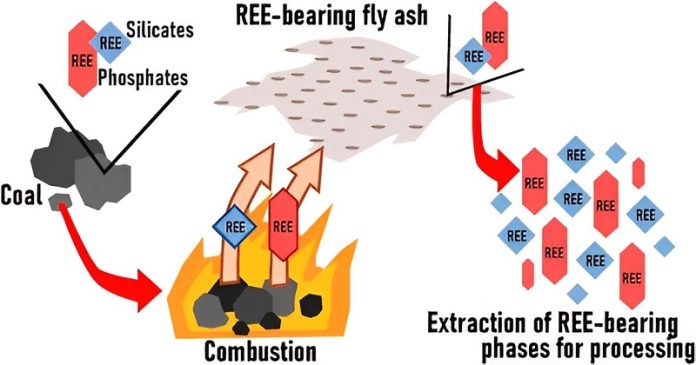

Bishop and his team have been focusing on coal ash, the waste left behind from coal-fired power plants.

While researchers have already explored REEs in coal waste from the U.S. and China, not much has been done on Canadian coal ash.

The team collected ash samples from power plants in Alberta and Saskatchewan to see how much REEs were present and how they could be extracted.

They found that the concentration of REEs in Canadian coal ash is similar to that found in other countries.

However, there was a question of whether the REEs were spread evenly throughout the ash or concentrated in certain minerals.

To answer this, Bishop used powerful X-ray technology at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) in Saskatchewan.

They focused on a rare earth element called yttrium, finding it was concentrated in specific minerals within the ash, particularly in silicates and phosphates like xenotime.

These minerals remain unchanged when coal is burned, making them easier to identify and potentially extract.

The team published their findings in Environmental Science and Technology.

This discovery is important because it gives researchers a clearer idea of how to recover REEs from coal ash more efficiently and in an environmentally friendly way.

Since yttrium is found in xenotime, a known ore mineral, existing methods for extracting REEs from ore could be adapted for use with coal ash.

According to Bishop, the amount of REEs that can be recovered will depend on how the extraction process is developed. While the concentration of REEs in coal ash isn’t extremely high, the sheer amount of waste coal ash available could make this a practical solution.

Unlike mined ores, the REEs in coal ash are distributed fairly evenly, so there’s no need for complex sorting.

Once perfected, the process of extracting REEs from coal ash would also be faster than opening new mines, which can take up to 17 years from exploration to production.

Recovering REEs from coal ash is also a big step toward creating a circular economy. While some coal ash is used in products like concrete, most of it ends up in landfills. By extracting rare metals from this waste, not only can we reduce environmental harm, but we also gain valuable materials needed for clean energy technologies.

“This process helps solve two problems,” Bishop says. “We can clean up the coal ash while getting the rare earth elements we need for green energy.”