Imagine being able to create tiny structures, like those in computer chips or medical devices, with the same ease and sustainability as printing on paper.

This is the exciting new frontier in microfabrication, a process crucial for making microscopic components in many of the devices we use every day.

Traditionally, microfabrication has relied on harmful chemicals that are difficult to dispose of safely.

However, scientists at the University of Chicago are changing this with an innovative, environmentally friendly method.

Led by Professor Bozhi Tian, the research team has developed a sustainable way to create and transfer tiny patterns using water and natural materials like paper.

Their work was recently published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Inspired by nature, such as how geckos can stick and unstick themselves from surfaces, the researchers discovered that water could be used as a green, non-toxic alternative to the harmful chemicals traditionally used in microfabrication.

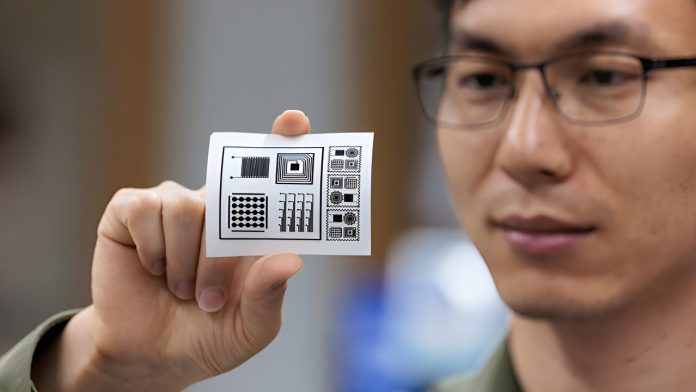

This new technique builds on an older method called salt-assisted photochemical synthesis but with a twist. Instead of using toxic agents, the team uses lasers to create patterns on paper that can easily be transferred using water.

“We found that water could gently and effectively separate the tiny patterns from their base materials,” said Professor Tian. This approach allowed the team to turn cellulose in paper into conductive carbon, which they could then use to create advanced sensors.

By carefully adjusting the carbon’s surface and using specific stimulators, they were able to enhance reactions in nanoscale materials, leading to a wide range of applications, from sensors to intricate medical devices.

The lead author of the study, Chuanwang Yang, a postdoctoral researcher in Tian’s lab, emphasized the significance of using water instead of toxic solvents, calling it a major step forward.

To make the process even more efficient, Yang developed a tool called the “Roll-to-roll Laser Writer.” This machine automates the laser writing and pattern transfer process, speeding up production and making it more reliable. Although this method might not replace the highly precise techniques needed for creating complex computer chips, the researchers believe it holds great potential for other applications, such as affordable, disposable sensors for medical tests or wearable devices.

Graduate student Pengju Li, who also worked on the project, highlighted how this method could improve the efficiency of making ultrathin medical devices, including those used for heart and neural stimulation.

By harnessing nature’s simplicity and using eco-friendly materials, this innovative method is set to transform microfabrication, paving the way for greener technologies in the future.