Earlier this year, NASA selected a rather interesting proposal for Phase I development as part of their NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program.

It’s known as Swarming Proxima Centauri, a collaborative effort between Space Initiatives Inc. and the Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is) led by Space Initiative’s chief scientist, Marshall Eubanks.

The concept was recently selected for Phase I development as part of this year’s NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program.

Similar to other proposals involving gram-scale spacecraft and lightsails, the “swarming” concept involves accelerating tiny spacecraft with a laser array to up to 20% the speed of light.

This past week, on the last day of the 2024 NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Symposium, Eubanks and his colleagues presented an animation illustrating what this mission will look like.

The video and their presentation provide tantalizing clues as to what scientists expect to find in the closest star system to our own.

This includes Proxima b, the rocky planet that orbits within its parent star’s circumsolar habitable zone (CHZ).

As we addressed in previous articles, the Swarming Proxima Centauri concept has evolved significantly over the past few years.

The concept emerged in 2017 as a proposal by the i4is named Project Lyra, which aimed to send tiny spacecraft to catch up with the interstellar object (ISO) ‘Oumuamua.

However, it has since evolved into a collaborative effort between the i4is and Space Initiatives Inc., a Florida-based aviation and aerospace component manufacturer dedicated to developing gram-based “femtospacecraft” – i.e., even tinier than nanospacecraft!

Not long ago, Eubanks and his colleagues produced research papers addressing some big questions about interstellar exploration, including communications and what we might learn from a flyby of Proxima b.

During the 2024 NIAC Symposium, which took place from September 10th to 12th in Pasadena, California, Eubanks and his colleagues had the opportunity to present their latest findings.

As the video illustrates, the swarm they envision will consist of a thousand “picospacecraft” (between nano and femto), which they’ve named “Coracles” (a small, rounded, lightweight boat).

The probes are solid, armored on one side, and covered with optical annuli (reflective material) on the other. They measure about two centimeters thick (0.8 inches) and four meters (about 13 feet) in diameter and weigh no more than a few grams each.

According to their NIAC proposal, these will be accelerated by a ~100 gigawatt (GW) laser array that will be available by mid-century. The probes are also equipped with side-mounted lasers to facilitate communications between them and mission controllers back on Earth.

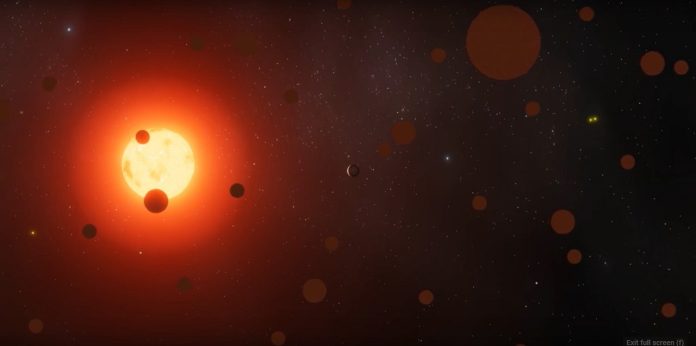

As Eubanks indicated during the presentation, there are actually a thousand probes in the animation and an artistically accurate depiction of the Proxima Centauri system.

The red dwarf is shown prominently as the probes approach the Proxima b, while Alpha Centauri AB is visible in the far background. Once the probes pass by the planet, we also get an accurate depiction of many scientists they expect to find:

“This is real-time. This is more or less what you would see expect for a redshift, a blushift, and then a redshift. And we had the artists do the planet as an ‘eyeball planet,’ where you have a central warm spot surrounded by a cold zone because we think this planet’s probably rotationally locked.”

As Eubanks further explained, their collaboration has already produced prototypes of their Coracle spacecraft. One was recently showcased at the World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow, while another is currently in Pasadena. While providing a run-down on the design of the individual spacecraft, Eubanks emphasized the importance of coherence and how the swarm’s configuration will facilitate communications and cohesion:

“Operational coherence is essential to making this mission work. By operational coherence, we mean that the whole set of probes acts as a unit. Now I notice that doesn’t mean photonic phase coherence – we won’t be able to do that.

But if we have good enough clocks and we have range measurement by lasers, we can determine where we are to a few centimeters. We can determine what the relative clocks are to more or less the same level. And [they] can then act as one thing.

“And the crucial part of that is we can do that with a lot of things, like taking pictures of the planet and so on. But the crucial part of that is what we call the wall of light.

The wall of light is when all the probes send one coherent set of photons back to Earth so they can be received altogether. We think we can get one kilobit per second data rate back, and we can, therefore, send something like four gigabytes a year back to Earth. And that’s enough to get good data and really understand the system.”

While the Swarming Proxima Centauri concept did not receive Phase II or III funding from the NIAC this year, it remains a project worthy of study and further development. Like Breakthrough Starshot and other lightsail proposals, it showcases what interstellar missions will look like in the coming decades.

In that respect, ideas like this also indicate that we are at a point in our history where exploring the nearest star systems is no longer considered a far-off idea that requires serious technological innovations to happen first.

Written by Matt Williams/Universe Today.