A new study reveals that building dams to protect coastal areas from flooding may actually lead to even worse flood events.

The research, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, focused on dams built in coastal estuaries—places where rivers meet the sea.

These large construction projects are becoming more popular worldwide as a way to reduce the effects of stronger storms, saltwater intrusion, and rising sea levels caused by climate change.

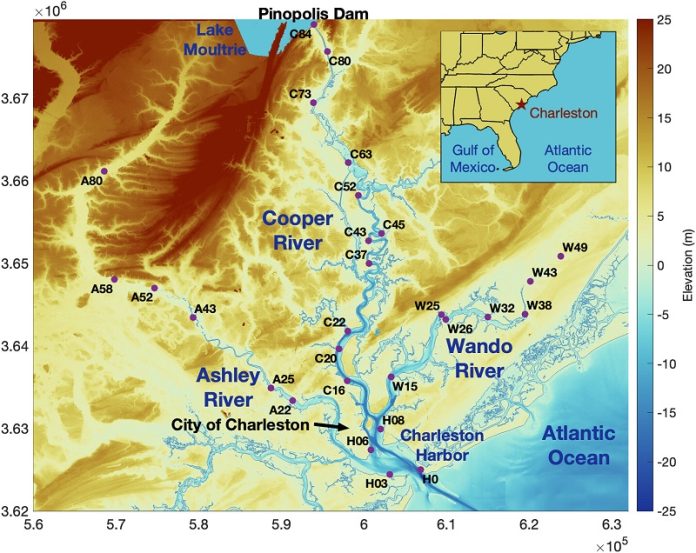

However, the study, which looked at data from Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, shows that these dams don’t always help.

In fact, depending on how long a storm surge lasts and how water flows, dams can either lower or increase the risk of flooding.

Lead author Steven Dykstra, from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, explained that storm surges usually get smaller as they move inland, but the shape of the land can change that. Estuaries are often shaped like a funnel, getting narrower as they stretch inland.

When a dam is built, it shortens the estuary with an artificial barrier, and that can actually reflect storm surge waves back, causing them to grow larger instead of smaller. Dykstra compared these waves to water splashing in a bathtub—sometimes the waves can slosh over the sides.

After studying Charleston Harbor, the researchers used computer models to test flood responses in 23 other estuaries, including dammed and natural systems like Cook Inlet in Alaska.

The models confirmed that the shape of the estuary and the way it is altered by dams are key factors in how storm surges behave.

When the waves are just the right size and last for the right amount of time, the presence of a dam can make them grow instead of shrink.

One surprising finding was that areas far from the coast can still be affected by coastal dams. In Charleston, for example, the highest storm surges happened more than 50 miles inland.

Dykstra noted that many people don’t realize they live in areas influenced by coastal flooding. With sea levels rising, more inland communities are discovering that they are not safe from coastal effects—and often, they find out during a major flood.

Other researchers from the University of South Carolina and California Polytechnic State University also contributed to the study.