In the depths of the Pacific Ocean, about 12,000 feet below the surface, lies a region called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

This area is covered with million-year-old rocks known as polymetallic nodules.

At first glance, these rocks might seem lifeless, but they are actually home to tiny sea creatures and microbes that have adapted to life in the dark.

Recently, scientists made an unexpected discovery: these deep-sea rocks are producing oxygen—a phenomenon they’re calling “dark oxygen.”

Typically, we think of oxygen as something created by plants and organisms that need sunlight to photosynthesize.

About half of the oxygen we breathe is made by tiny plants called phytoplankton near the ocean’s surface.

But finding oxygen production deep in the ocean, where sunlight doesn’t reach, is completely surprising.

When the researchers first noticed this, they thought it might be a mistake. Jeffrey Marlow, a biology professor at Boston University, was one of the scientists involved in the study. Marlow, an expert on microbes that live in extreme environments, initially suspected that these tiny organisms might be responsible for the oxygen.

To test this, the team used special chambers to enclose the seawater, sediment, polymetallic nodules, and the organisms living there. They measured how oxygen levels changed over 48 hours.

Normally, if organisms are breathing in oxygen, the levels would decrease. But instead, the oxygen levels increased. After repeated experiments, the researchers confirmed that the oxygen production was real.

The research team was on a mission to learn more about the ecology of the CCZ, a vast area that stretches between Hawaii and Mexico.

Their work was part of an environmental survey sponsored by The Metals Company, a deep-sea mining firm interested in harvesting these rocks for their valuable metals. But what the scientists found was that the oxygen wasn’t mainly due to microbial activity. Instead, it seemed to be linked to the rocks themselves.

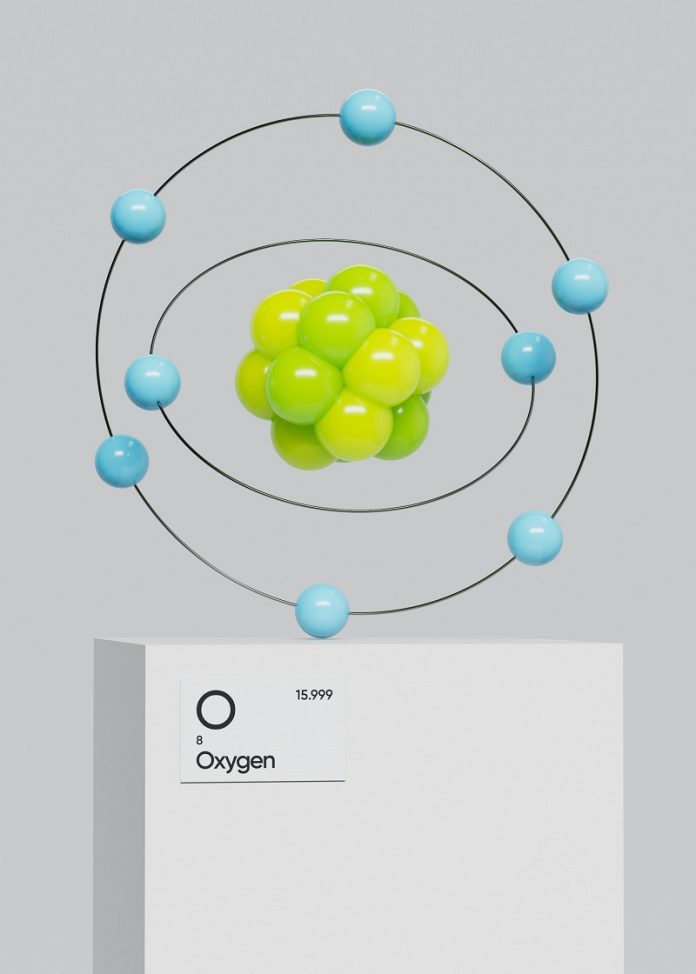

Polymetallic nodules contain rare metals like copper, nickel, cobalt, iron, and manganese. The study suggests that these metals might be triggering a process called “seawater electrolysis,” where unevenly distributed metal ions create an electrical charge—much like a battery. This charge has enough energy to split water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen, creating the “dark oxygen.”

The implications of this discovery are significant. It raises questions about how much oxygen these rocks produce, how it affects the surrounding ecosystem, and what might happen if deep-sea mining disturbs this delicate balance. Some countries and environmental groups are already calling for a halt to mining in the CCZ due to concerns about potential damage to this largely unexplored ecosystem.

The CCZ is also an intriguing area for scientists studying life in extreme environments, like those found on other planets and moons.

The conditions in the CCZ, with its high pressure, darkness, and metal-rich rocks, are similar to what we might find on places like Saturn’s moon Enceladus or Jupiter’s moon Europa.

This discovery could help scientists understand how life might exist in such alien environments.

Ultimately, this finding flips our understanding of the deep sea, showing that it’s not just a place where dead material sinks and gets eaten.

Instead, it’s a site of production, with potential implications for both our planet and the search for life beyond Earth.