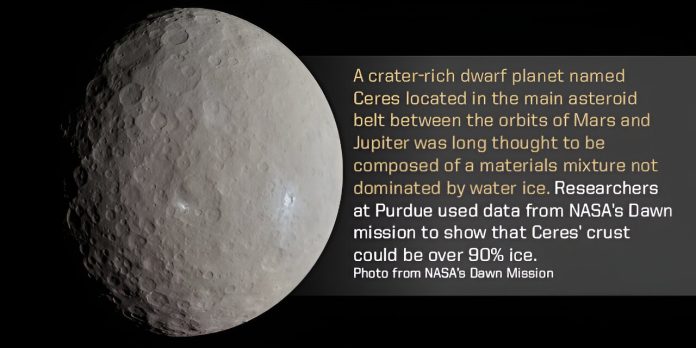

Ceres, the largest asteroid in our solar system, has long intrigued scientists.

Since its discovery in 1801 by astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, experts have debated what this giant, crater-covered object is made of. For a long time, the craters on Ceres suggested that it couldn’t contain much ice, but new research is challenging that idea.

A team of scientists from Purdue University and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) now believe that Ceres is actually a very icy object, possibly once covered by a muddy ocean.

This discovery, led by Ph.D. student Ian Pamerleau and assistant professor Mike Sori, was published in Nature Astronomy.

Their research used computer models to simulate how craters on Ceres change over billions of years, revealing surprising insights about its icy nature.

“We think there’s a lot of water-ice just below the surface of Ceres,” explained Sori.

“As you go deeper, it gets less icy, but the ice is stronger than we thought if mixed with just a bit of rock. This helps explain why the craters on Ceres don’t flatten out quickly, which was previously puzzling.”

For many years, scientists assumed Ceres was relatively dry, with less than 30% ice. However, Sori’s team now believes that the surface is closer to 90% ice.

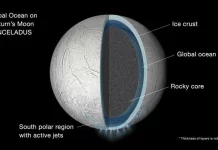

This discovery suggests that Ceres used to be an “ocean world,” similar to Jupiter’s moon Europa, but with a dirty, muddy ocean that eventually froze into a solid crust.

Pamerleau described how their computer models showed that even solid materials can slowly flow over time, with ice being more prone to this flow than rock. When craters form, they create deep bowls that put a lot of stress on the surface.

Over time, these stresses cause the craters to become shallower through a process called “relaxation.” Earlier studies concluded that because Ceres’ craters hadn’t relaxed much, its surface couldn’t be very icy.

But Pamerleau and Sori’s new models suggest that if the ice is mixed with some rock, it would barely flow, even over billions of years. This could explain why Ceres, despite being ice-rich, still has well-preserved craters.

Sori’s research focuses on understanding the interiors of planets and how they connect to what we see on their surfaces. His work spans many objects in our solar system, including the Moon, Mars, and icy bodies like Ceres.

He emphasized that Ceres, despite being called an asteroid, is more like a planet. It’s a nearly round body, about 950 kilometers in diameter, with features like craters, volcanoes, and landslides.

The NASA Dawn mission, launched in 2007, was the first spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations: Vesta and Ceres. Although it didn’t reach Ceres until 2015, Dawn’s observations have been crucial in understanding this icy world.

Using data from Dawn, Pamerleau and Sori’s team were able to model the structure of Ceres’ crust. They found that the best explanation for the lack of crater relaxation is a crust that is very icy near the surface but gradually becomes less icy as you go deeper. This structure could help us understand other icy worlds in our solar system.

Sori highlighted the significance of this discovery: “Ceres might be the most accessible icy world in the universe. It’s a great target for future missions, and its surface could hold clues to an ancient ocean, now frozen, just waiting to be explored.”

Source: Purdue University.