Jupiter’s moon, Ganymede, is a fascinating celestial body.

Measuring 2,634 km (1,636 mi) in diameter, it is also the largest satellite in the Solar System and even larger than Mercury, which measures 2,440 km (1,516 mi) in diameter.

Like Europa, it has an interior ocean and is one of the few bodies in the Solar System (other than the gas giants) with an intrinsic magnetic field.

The presence of this field also means Ganymede experiences aurorae circling the regions around its northern and southern poles due to interaction with Jupiter’s magnetic field.

In addition, based on its surface craters, scientists believe that Ganymede experienced a powerful impact with an asteroid about 4 billion years ago.

This asteroid was about 20 times larger than the Chicxulub asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs, or the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (ca. 66 million years ago).

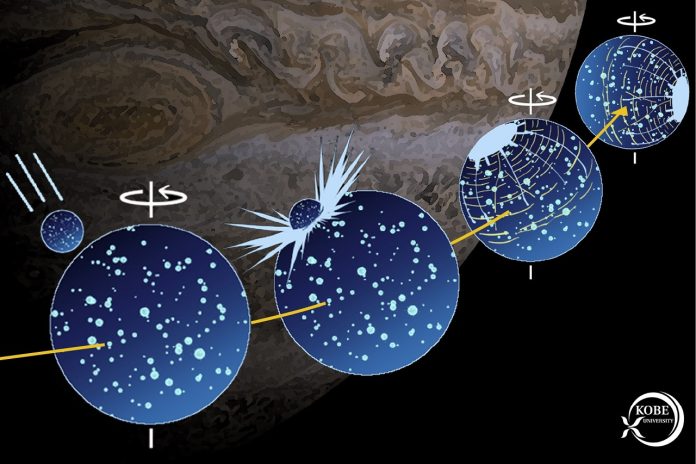

According to a recent study by Naoyuki Hirata of Kobe University, this impact occurred almost precisely on the meridian farthest away from Jupiter.

This caused a reorientation of Ganymede’s rotational axis and allowed Hirata to determine exactly what type of impact took place.

Naoyuki Hirata is an assistant professor with the Department of Planetology at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Science. His paper, “Giant impact on early Ganymede and its subsequent reorientation,” recently appeared in Science Reports.

Since the Pioneer 10 and 11 and the Voyager 1 and 2 probes flew through the Jupiter system in the 1970s, scientists have known that large parts of Ganymede’s surface are covered by furrows that form concentric circles around a single spot.

This led researchers in the 1980s to conclude that these were the result of a major impact event.

The exact nature of this impact and its effects on Ganymede has been the subject of debate ever since. As Hirata said in a Kobe University press release:

“The Jupiter moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto all have interesting individual characteristics, but the one that caught my attention was these furrows on Ganymede.

We know that this feature was created by an asteroid impact about 4 billion years ago, but we were unsure how big this impact was and what effect it had on the moon.”

Using data obtained by the New Horizons mission of Pluto, Hirata drew on similarities with an impact event on Pluto that caused a shift in the (dwarf) planet’s rotational axis.

As a specialist who simulates impact events on moons and asteroids, Hirata was able to calculate what kind of impact would have caused Ganymede’s orientation to shift.

According to his estimates, the asteroid had a diameter of around 300 km (~186.5 mi) that created a crater measuring between 1,400 and 1,600 km (870 and 995 mi) in diameter before the debris resettled on the surface.

Evidence of this impact is visible today in the center of the furrow system on the anti-Jovian side of Ganymede (the hemisphere facing away from Jupiter) and currently measures roughly 1,000 km (662 mi) in diameter. Looking ahead, Hirata hopes to learn how this impact could have affected the moon’s evolution, particularly where its internal ocean is involved:

“I want to understand the origin and evolution of Ganymede and other Jupiter moons. The giant impact must have had a significant impact on the early evolution of Ganymede, but the thermal and structural effects of the impact on the interior of Ganymede have not yet been investigated at all. I believe that further research applying the internal evolution of ice moons could be carried out next.”

The ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission is currently en route to Jupiter and will establish orbit around Ganymede by 2034. The observations it makes over the next six months will help shed light on these and other questions regarding Ganymede and its sibling satellites, Europa and Callisto – not the least of which is whether or not these “Ocean Worlds” can support life.

Written by Matt Williams/Universe Today.