Researchers at UNSW have made an exciting breakthrough using silk from domestic silk moths.

This silk, transformed into a special jelly-like material called microgel, has the potential to help regenerate heart tissue and assist in healing wounds.

The innovation could be a game-changer for people recovering from heart attacks and those with chronic wounds.

The team at UNSW Graduate School of Biomedical Engineering, led by Associate Professor Jelena Rnjak-Kovacina, has turned silk into microgel using light.

This process is similar to how Jello is made from a liquid, but instead of using heat, they use light.

The result is a jelly-like substance that can be easily tolerated by the body and supports the growth of cells and tissues.

The main goal of this research is to help people who have had heart attacks. During a heart attack, part of the heart muscle dies, weakening the heart and making it harder for it to pump blood. Over time, this can lead to heart failure.

The microgel could be injected into the heart muscle to help it regenerate, supporting the heart and improving its function.

“Our microgels are made entirely of silk, but we can also load them with other molecules such as drugs and proteins that help control inflammation or promote tissue growth,” says Associate Professor Rnjak-Kovacina. This means the microgel not only supports damaged tissue but also delivers substances that promote healing and regeneration.

The microgel mimics the properties of human tissue and interacts with cells in the body. It stimulates the right inflammatory responses to promote cell growth and tissue regeneration. Additionally, it can be loaded with growth factors that help form new blood vessels.

Normally, these growth factors degrade quickly when injected into the body. However, the microgel allows for a slower release, leading to better results.

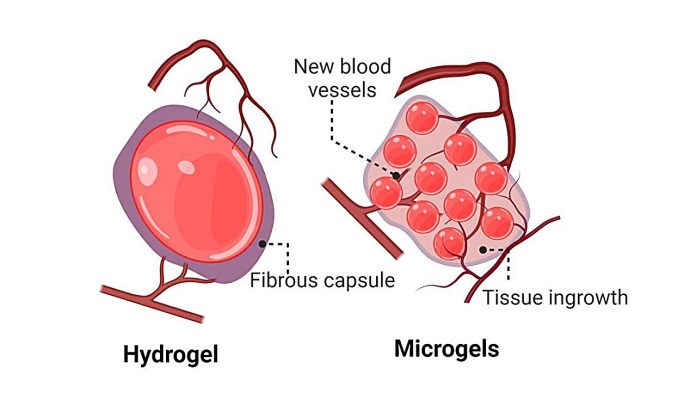

One significant improvement with this new microgel is its porous nature. This porosity allows cells to move around and grow within the material more effectively, solving a problem that has hindered similar research for decades.

The microgel also mimics the complexity of the body better than previous materials. Instead of being one uniform lump, the microgel consists of many tiny, individual elements that can be different, much like the body’s tissues.

The researchers are already conducting further studies to inject the microgel into the hearts of mice. If successful, they will move on to testing in larger animals like pigs, and eventually, clinical trials in humans, which could take about five years.

In the meantime, there are other exciting uses for the microgel. It could be used as a skin-wound healing agent, which is less invasive than heart injections.

This application could benefit people with serious burns or chronic wounds, like diabetic ulcers that are difficult to heal.

Moreover, the microgel could help develop human tissue models in the lab. These models would mimic real human tissue and could be used to test new drugs and treatments, providing a huge benefit for medical research.

This innovative use of silk could revolutionize how we treat heart damage and chronic wounds.

By combining the strength and versatility of silk with advanced biomedical engineering, the UNSW researchers are paving the way for new treatments that could save lives and improve the quality of life for many patients.

The future of healing hearts and wounds looks bright, thanks to this supercharged silk.

If you care about pain, please read studies about vitamin K deficiency linked to hip fractures in old people, and these vitamins could help reduce bone fracture risk.

For more information about wellness, please see recent studies that Krill oil could improve muscle health in older people, and eating yogurt linked to lower frailty in older people.