Scientists have made an exciting discovery at the landing site of China’s Chang’e-6 mission on the moon’s farside.

The mission, which is part of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, successfully returned to Earth with nearly 2 kilograms of lunar soil from the South Pole-Aitken (SPA) basin.

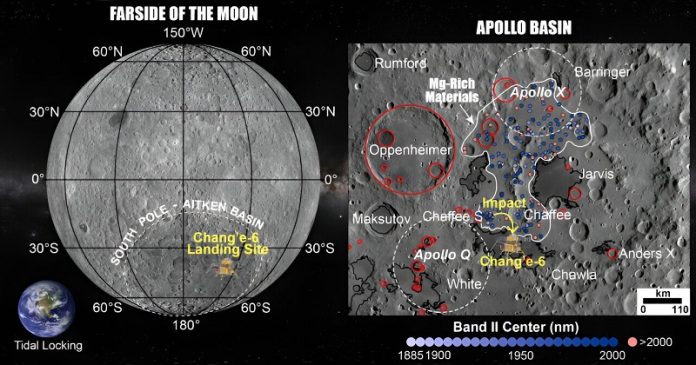

This area is one of the largest and oldest impact basins on the moon and is located on the far side, opposite the side that always faces Earth.

Unlike previous lunar missions that brought back samples from the moon’s nearside, this is the first mission to return with samples from the far side.

These new samples could help scientists solve the mystery of why the two sides of the moon are so different—a puzzle known as the “lunar dichotomy.”

While scientists have long studied volcanic activity on the moon, the Chang’e-6 mission has revealed something more intriguing: hidden magmatic activity beneath the surface.

Magmatism refers to the movement and solidification of magma (molten rock) beneath the surface, which eventually forms large rock formations called plutons.

A research team from the University of Hong Kong (HKU), led by Dr. Yuqi Qian, along with international collaborators, has used remote sensing data to study this magmatic activity at the Chang’e-6 landing site.

Their findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The study uncovered widespread intrusive magmatism in the SPA basin. This magmatism takes several forms, such as sills (horizontal layers of solidified magma) under crater floors and dikes (vertical sheets of magma) that form rings and lines, visible in gravity data. These formations suggest that the SPA basin’s crust is thick enough to support the intrusion of magma.

The Chang’e-6 mission likely collected samples of these plutonic rocks, which were delivered to the sampling site by nearby impact craters. Among these samples, the researchers identified materials rich in magnesium, known as Mg-suite rocks. These Mg-rich materials are particularly important because they could help scientists understand the origin of mysterious rocks on the moon that lack certain elements (like KREEP) and how the moon’s crust was built over time.

Professor Xianhua Li from the Chinese Academy of Science highlighted the importance of this discovery, stating that it provides a crucial framework for studying the plutonic rocks in the Chang’e-6 samples. Understanding the formation and timing of these rocks could give new insights into the moon’s early history and evolution.

Professor Guochun Zhao, a leading scientist in the study, emphasized that HKU’s involvement in China’s Lunar Exploration Program is a significant step toward making Hong Kong an international hub for scientific research and innovation.

This groundbreaking research opens new doors for understanding the moon’s history and brings us closer to solving the long-standing mystery of the lunar dichotomy.