Astronomers have unveiled new, detailed images of Polaris, commonly known as the North Star, revealing a surface dotted with bright and dark spots.

This remarkable discovery was made possible by the advanced technology at Georgia State University’s Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array.

The findings were recently published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Polaris has long been a crucial point of reference for navigation, as Earth’s North Pole aligns with it. But beyond its guiding role, Polaris is a fascinating star in its own right.

It is the brightest star in a triple-star system and is known as a pulsating variable star, meaning it gets brighter and dimmer over time as it expands and contracts in size every four days.

Polaris belongs to a special class of stars called Cepheid variables. These stars are incredibly important to astronomers because they serve as “standard candles” for measuring distances in space.

The period of a Cepheid’s pulsation is directly related to its true brightness: brighter Cepheids pulsate more slowly, while fainter ones pulsate more quickly.

By comparing how bright a Cepheid appears from Earth to its known true brightness, astronomers can determine how far away it is. This, in turn, helps scientists measure the distances to galaxies and even gauge the expansion rate of the universe.

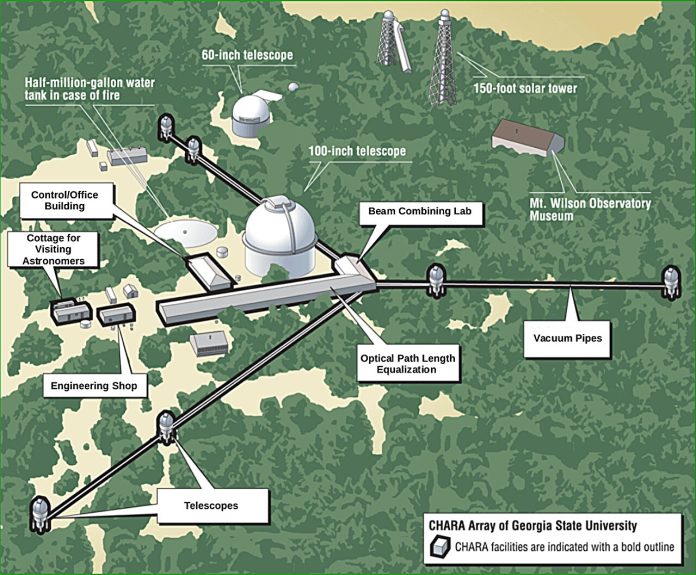

A team of researchers, led by Nancy Evans from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, used the CHARA Array to study Polaris more closely. The CHARA Array is located at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory in southern California and consists of six telescopes spread across the mountaintop.

By combining the light collected by these telescopes, the CHARA Array can act like a single, enormous telescope with a diameter of 330 meters.

This capability allowed the team to observe a faint companion star that orbits Polaris every 30 years—a task made difficult by the small distance between the stars and the significant difference in their brightness.

Using the MIRC-X camera, which was developed by astronomers from the University of Michigan and Exeter University in the UK, the team was able to capture detailed images of Polaris.

These images revealed that Polaris is about five times more massive than the sun and has a diameter 46 times larger than our solar system’s central star.

The most surprising finding was the discovery of large bright and dark spots on the surface of Polaris. These spots, which change over time, offer the first-ever glimpse of what the surface of a Cepheid variable star looks like.

Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array, explained that these spots might be linked to a 120-day variation in the star’s measured velocity, possibly due to its rotation.

John Monnier, an astronomy professor at the University of Michigan, shared the team’s plans to continue observing Polaris to better understand what causes these spots to form on the star’s surface.

These groundbreaking observations were made as part of an open access program at the CHARA Array, which allows astronomers from around the world to apply for observation time through the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab).

This discovery not only deepens our understanding of Polaris but also highlights the power of advanced astronomical technology in revealing the mysteries of the universe.