Astrophysicists from around the world, including researchers from the University of Zurich, have come up with an exciting new way to detect massive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

Their method involves analyzing gravitational waves created by smaller black holes.

This research has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The mystery of supermassive black holes

Supermassive black holes, which sit at the centers of galaxies, are one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy.

Scientists aren’t sure how they formed. They might have started out huge when the universe was young, or they could have grown over time by pulling in matter and other black holes.

When a supermassive black hole is about to consume another big black hole, it emits gravitational waves, which are ripples in spacetime that travel through the universe.

Gravitational waves have been detected recently, but only from small black holes that are the remnants of stars.

Detecting signals from pairs of big black holes is still impossible with current technology because the gravitational waves they emit are at very low frequencies that our detectors can’t pick up.

Future detectors, like the space-based ESA-led mission LISA, will help somewhat, but even they won’t be able to detect the most massive black hole pairs.

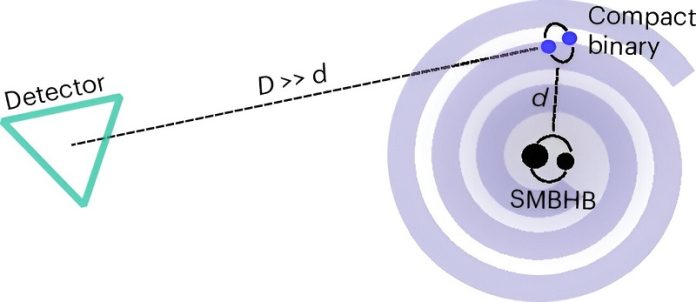

The team of astrophysicists, including former students from the University of Zurich, proposes a new method to detect pairs of the biggest black holes. They suggest analyzing the gravitational waves created by pairs of nearby small black holes, which are the remnants of collapsed stars.

This method requires a special detector called a deci-Hz gravitational-wave detector. It would allow scientists to discover the biggest supermassive black hole pairs, which are currently hard to detect.

Jakob Stegmann, the lead author of the study, explains that their idea is similar to how a radio works. They propose using the signal from pairs of small black holes like how radio waves carry music.

The supermassive black holes are like the music encoded in the frequency of the detected signal. Stegmann started this work as a visiting student at the University of Zurich and is now at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics as a postdoctoral researcher.

The novel aspect of this idea is to use high frequencies, which are easier to detect, to probe lower frequencies that we currently can’t pick up.

A beacon for bigger black holes

Recent results from pulsar timing arrays already suggest the existence of merging supermassive black hole pairs, but this evidence is indirect and comes from the collective signal of many distant pairs.

The new method aims to detect individual supermassive black hole pairs by leveraging the small changes they cause in the gravitational waves emitted by nearby small black holes. This way, the small black hole pairs work like beacons, revealing the existence of the bigger black holes.

By detecting these tiny changes, scientists could identify previously hidden supermassive black hole pairs with masses ranging from 10 million to 100 million times that of our sun, even from vast distances.

Lucio Mayer, a co-author of the study and a black hole theorist at the University of Zurich, notes that as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) project moves forward, the scientific community needs to consider the best strategies for future gravitational wave detectors.

Studies like this provide strong motivation to prioritize a deci-Hz detector design, which could revolutionize our ability to detect massive black holes.