In an exciting discovery, scientists have found evidence of a massive underground reservoir of water on Mars.

This reservoir is so large that it could potentially fill entire oceans on the planet’s surface.

However, there’s a catch—this water is buried deep underground, making it nearly impossible to reach with current technology.

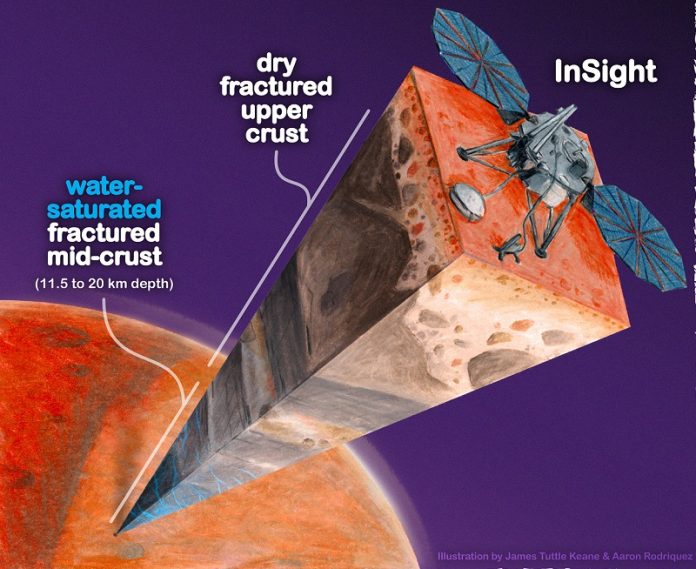

The research team, using data from NASA’s InSight lander, was able to estimate the amount of water hidden beneath the Martian surface.

They believe that if this water were to spread out evenly, it could cover the entire planet to a depth of 1 to 2 kilometers, which is about a mile deep.

This is a significant finding for scientists studying Mars, as it sheds light on where the planet’s water may have gone after its surface oceans disappeared over 3 billion years ago.

Despite this exciting discovery, the underground water won’t be of much help to future Mars explorers or colonies.

The water is trapped in tiny cracks and pores in the rock, located between 11.5 and 20 kilometers (7 to 12 miles) below the surface. Even on Earth, drilling a hole a kilometer deep is extremely challenging, so reaching this water on Mars would be incredibly difficult with current technology.

While the reservoir might not be easy to access, it still offers valuable insights into Mars’ history and geology.

Understanding where water is located on Mars and how much of it exists is crucial for scientists trying to piece together the planet’s past climate and geological changes.

Vashan Wright, an assistant professor at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and one of the researchers involved, emphasized the importance of this discovery. “Understanding the Martian water cycle is critical for understanding the evolution of the climate, surface, and interior,” Wright said. “A useful starting point is to identify where water is and how much is there.”

The study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, involved a team of researchers from various institutions, including UC Berkeley and Scripps Oceanography.

They used a mathematical model similar to those used on Earth to map underground aquifers and oil fields. By analyzing seismic data collected by InSight, the team concluded that a layer of fractured rock deep within Mars’ crust is likely saturated with liquid water.

This discovery suggests that much of Mars’ water didn’t escape into space, as some scientists previously thought, but instead seeped deep into the planet’s crust. While we still haven’t found evidence of life on Mars, this underground water could provide a potential habitat for life, similar to how life exists in deep mines and the ocean floor on Earth.

NASA’s InSight mission, which ended in 2022, provided invaluable data about Mars’ interior, including the thickness of its crust, the depth of its core, and the composition of its mantle.

This new discovery of underground water is just one of the many groundbreaking findings from the mission, offering new clues about the Red Planet’s mysterious past.