Scientists from the University of Oxford and other institutions have discovered a remarkable new fossil species, Shishania aculeata, dating back 500 million years.

This discovery sheds light on the early evolution of mollusks, a diverse group that includes snails, clams, squids, and octopuses.

The fossils were found in eastern Yunnan Province, southern China, in rocks from the early Cambrian period, around 514 million years ago.

Shishania aculeata was a small, flat slug without a shell but covered in protective spiny armor made of chitin. Chitin is a material found in the shells of modern crabs, insects, and some mushrooms.

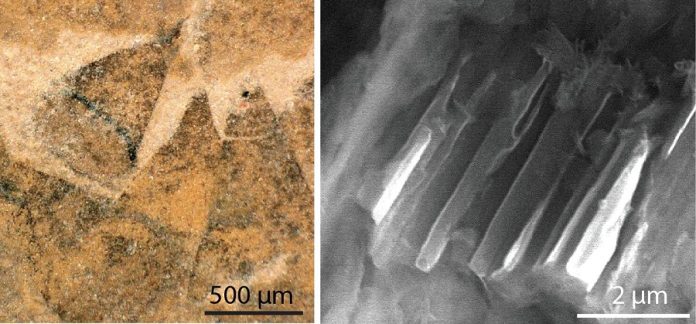

Shishania fossils, only a few centimeters long, reveal a unique view of early mollusk ancestors. Unlike most mollusks today, Shishania did not have a shell.

Instead, it had a muscular foot, similar to modern slugs, which it used to move around the ancient seafloor. The bottom of its body was naked, further highlighting its primitive features.

Present-day mollusks are incredibly diverse, ranging from snails and clams to highly intelligent creatures like squids and octopuses.

This diversity began during the Cambrian Explosion, a period of rapid evolutionary change when all major animal groups started to diversify. However, fossils from this time are rare, making discoveries like Shishania aculeata crucial for understanding mollusk evolution.

Associate Professor Luke Parry from the University of Oxford explained that studying Shishania helps scientists understand what the common ancestor of different mollusks might have looked like. The fossil shows that early mollusk ancestors were armored spiny slugs, which eventually evolved into the shelled mollusks we see today.

The discovery was made by Guangxu Zhang, a recent Ph.D. graduate from Yunnan University. Initially, Zhang thought the fossils were insignificant, but upon closer examination with a magnifying glass, he noticed their unique spiny structure. Further analysis in the lab confirmed that these were indeed ancient mollusks.

Shishania’s spines, or sclerites, show microscopic details that provide insight into how they were formed. These spines had an internal system of tiny canals, indicating they were secreted by microvilli, similar to how some invertebrate animals create hard parts. This process is comparable to a natural 3D printer, allowing the formation of hard parts for defense or movement.

Interestingly, while some present-day mollusks like chitons have hard spines and bristles made of calcium carbonate, Shishania’s spines were made of organic chitin. This characteristic links Shishania to other animal groups like brachiopods and bryozoans, which also have chitinous structures.

Professor Parry noted that Shishania shows how the spines and spicules in some modern mollusks evolved from organic sclerites, similar to those of annelids, such as earthworms. This discovery provides a glimpse into the early evolutionary stages of mollusks and their divergence from common ancestors.

Co-author Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol emphasized that Shishania offers a rare look into mollusk evolution before the development of shells. The fossil record of soft-bodied mollusks is limited, making these findings from Yunnan Province exceptionally valuable.

Xiaoya Ma, a co-corresponding author from Yunnan University and the University of Exeter, highlighted that the Cambrian rocks of Yunnan Province are a treasure trove of early animal fossils. Discoveries like Shishania aculeata reveal significant details about the diverse and ancient world of early mollusks.

Source: University of Oxford.