Researchers at UC Davis Health have uncovered a surprising new way that harmful bacteria like Salmonella find their way into the body: by following electric currents in the gut.

This discovery, published in Nature Microbiology, sheds light on how these pathogens navigate the complex environment of the intestines to cause infections.

Salmonella is a dangerous pathogen responsible for about 1.35 million illnesses and 420 deaths in the United States every year.

To cause an infection, Salmonella must cross the protective barrier of the gut lining. But with over 100 trillion good bacteria (known as commensals) in the intestines, Salmonella faces tough odds.

To understand how Salmonella manages to breach this barrier, the researchers studied the movement of a strain called S. Typhimurium, comparing it to harmless E. coli bacteria.

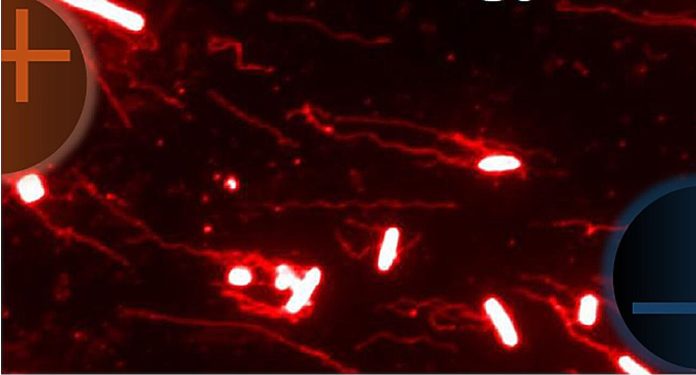

They discovered that Salmonella uses a process called galvanotaxis, or electrotaxis, to detect and move toward electric signals in the gut. These electric fields guide the bacteria to specific areas where they can find openings to invade the body.

The intestine is a complex and varied environment. It includes two key areas: the villus epithelium, which is responsible for absorbing nutrients, and the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE), which contains M cells.

These M cells are part of the immune system’s first line of defense, sampling antigens to protect the body from harmful microbes and substances.

The researchers found that Salmonella is attracted to the electric fields in the FAE, which serve as entry points for the bacteria. Once Salmonella reaches these areas, it can breach the gut lining and cause an infection.

Interestingly, the study revealed that Salmonella and E. coli respond differently to these bioelectric fields. While E. coli tends to stay near the villi, Salmonella is drawn to the FAE. This difference in behavior highlights how Salmonella takes advantage of the gut’s natural electric fields to find the best spots for invasion.

Previous studies have shown that bacteria often move in response to chemical signals, a process known as chemotaxis. However, this new research suggests that Salmonella uses a different mechanism—galvanotaxis—to locate entry points in the gut, bypassing the usual chemical pathways.

This discovery could have important implications for understanding and treating chronic gut disorders like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBD is thought to be caused by an abnormal immune response to good bacteria in the gut.

The researchers speculate that the abnormal bioelectric activity in the gut could be linked to conditions like IBD, potentially opening new avenues for treatment and prevention.

“This new mechanism represents a sort of ‘arms race’ between pathogens and the human body,” said Min Zhao, the study’s senior author.

“Understanding how Salmonella and other bacteria exploit these electric fields could lead to new ways to prevent and treat infections and gut disorders.”