For years, astronomers have been puzzled by a strange pattern observed in galaxies. No matter the age, shape, or size of a galaxy, the density of matter—both stars and dark matter—seemed to decrease at the same rate from the center to the outer edges.

This uniformity was baffling, as galaxies are incredibly diverse, and it led scientists to suspect that stars and dark matter were somehow working together in mysterious ways.

This idea, often referred to as a “conspiracy,” suggested that dark matter and stars were compensating for each other to create such consistent mass structures across different galaxies.

However, an international team of astronomers, including researchers from Australia, the UK, Austria, and Germany, has just debunked this longstanding theory.

Their findings, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveal that the similarity in density isn’t due to a cosmic conspiracy between stars and dark matter. Instead, it might be due to the way astronomers have been measuring and modeling galaxies.

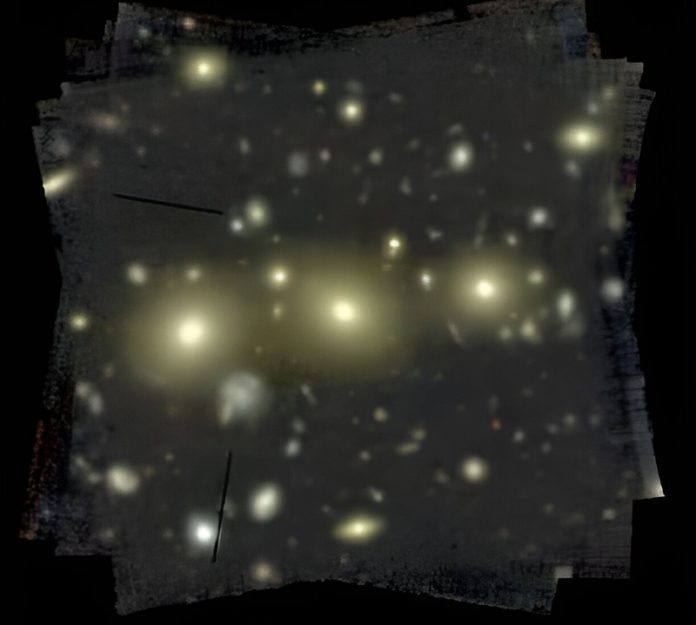

The team made this discovery by studying 22 middle-aged galaxies located around four billion light-years away. Using the Very Large Telescope in Chile, they were able to observe these galaxies in incredible detail. The data they collected allowed them to create more complex models of galaxies, which better reflect the true diversity of these cosmic structures.

Dr. Caro Derkenne, the lead author of the study and a researcher at Macquarie University in Australia, explained that previous models were too simple and made too many assumptions. “Galaxies are complicated,” she said, “and if we don’t account for this complexity, we end up measuring the wrong things.” The new models, which ran on the powerful OzStar supercomputer at Swinburne University, took into account the many differences between galaxies, revealing that the earlier observed uniformity was likely a result of oversimplified models.

This breakthrough not only solves a 25-year-old mystery in astronomy but also highlights the importance of using more advanced tools and models to study the universe. Dr. Derkenne, who is now applying her skills in astronomy to big data challenges in the Australian Public Service, believes that the methods used in this research can also help tackle real-world problems.

The project, known as MAGPI (Middle Ages Galaxy Properties with Integral field spectroscopy), used a special instrument called MUSE on the Very Large Telescope. MUSE collects detailed data from galaxies, allowing astronomers to analyze them pixel by pixel, revealing new insights into how galaxies are truly structured.

This study is a testament to the power of collaboration and advanced technology in solving some of the most challenging questions in science.