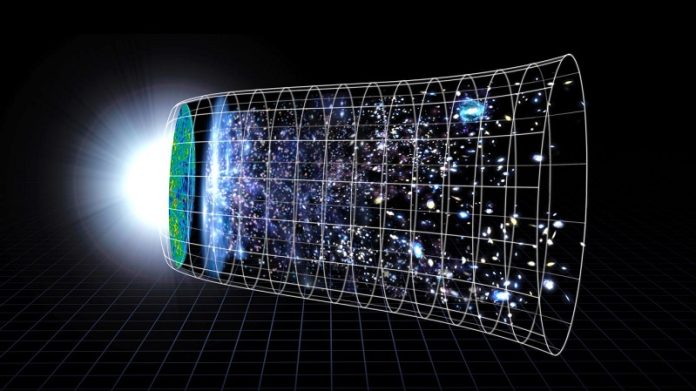

For years, astronomers have debated how fast our universe is expanding—a key question that helps us understand the history and future of the cosmos.

This rate is known as the “Hubble constant,” named after Edwin Hubble, who first discovered in 1929 that the universe is expanding.

However, two major methods used to measure the Hubble constant have produced conflicting results, leading to what scientists call the “Hubble tension.”

Some even wondered if our current model of the universe might be missing something important.

But now, new data from NASA’s powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) might help resolve this tension and suggest that our model of the universe still holds true.

In a recent study, University of Chicago cosmologist Wendy Freedman and her team analyzed data from the JWST to measure how fast the universe is expanding today.

They focused on ten nearby galaxies and calculated a new value for the Hubble constant: 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec. This value aligns closely with another method for measuring the Hubble constant, suggesting that there might not be a significant conflict after all.

“Based on these new JWST data and using three independent methods, we do not find strong evidence for a Hubble tension,” said Freedman, a renowned astronomer. “It looks like our standard cosmological model for explaining the evolution of the universe is holding up.”

The concept of Hubble tension arises from differences in how astronomers measure the expansion rate of the universe.

One method involves studying the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is the leftover light from the Big Bang. This method currently estimates the Hubble constant to be about 67.4 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The second method, which Freedman specializes in, involves measuring the expansion of nearby galaxies. This method has historically given a higher estimate—around 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The gap between these two numbers led some scientists to believe that our understanding of the universe might be incomplete.

The James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021, is a new and powerful tool for astronomers.

Freedman and her colleagues used the telescope to take measurements of ten nearby galaxies, providing fresh data to help determine the universe’s expansion rate.

To ensure accuracy, they used three different methods. The first method involved Cepheid variable stars, which change their brightness in a predictable way. The second method, called the “Tip of the Red Giant Branch,” relies on the fact that certain stars reach a fixed brightness before they die.

The third, newer method uses carbon stars, which have consistent brightness in the near-infrared spectrum. All three methods gave results that were consistent with each other and close to the value obtained from the cosmic microwave background method.

“Getting good agreement from three completely different types of stars is a strong indicator that we’re on the right track,” Freedman said.

Although these findings are promising, the debate over the Hubble constant isn’t completely settled. Future observations with the JWST will be crucial to confirm or refute the Hubble tension and understand what it means for our understanding of the universe.

So, while there’s still more to learn, the latest data suggests that our current model of the universe might be just fine after all.

Source: University of Chicago.