Microplastics and nanoplastics are everywhere—in our food, water, and even the air we breathe.

These tiny plastic particles have been found in various parts of our bodies, from our testicles to our brains.

Now, researchers at the University of British Columbia have developed a simple, low-cost tool to measure the amount of plastic released from everyday items like disposable cups and water bottles.

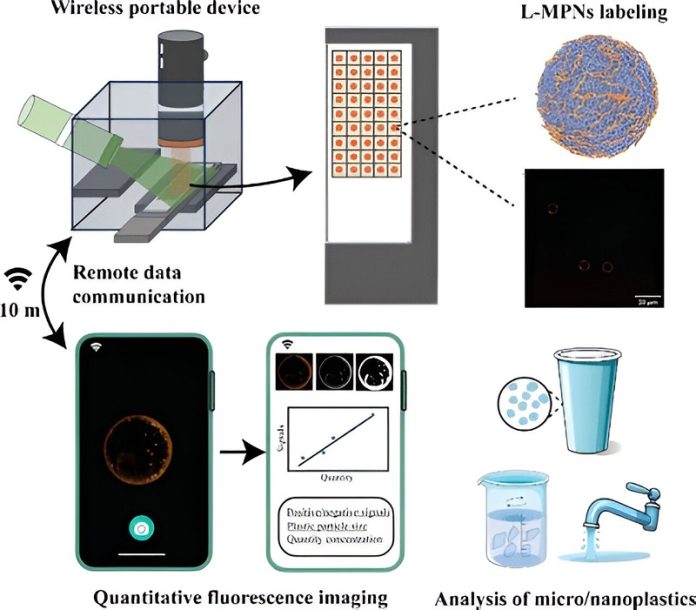

The new device, which works with an app, uses fluorescent labeling to detect plastic particles that are too small to see with the naked eye, ranging from 50 nanometers to 10 microns in size.

It can deliver results in just minutes. The details of this breakthrough were published in the journal ACS Sensors.

“The breakdown of larger plastic pieces into microplastics and nanoplastics is a growing concern because of the risks they pose to our food, ecosystems, and health,” said Dr. Tianxi Yang, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems, who developed the tool.

“This new method allows for quick and affordable detection of these plastics, which could help protect our health and the environment.”

Micro- and nanoplastics are created when larger plastic items, like lunchboxes, cups, and utensils, degrade over time. These tiny particles are especially worrisome for human health because they can absorb toxins and penetrate deep into our bodies, crossing biological barriers that usually protect us.

Traditionally, detecting these plastics requires expensive equipment and trained experts. Dr. Yang’s team wanted to make this process faster, easier, and more accessible to everyone.

They developed a small, biodegradable, 3D-printed box that contains a wireless digital microscope, a green LED light, and an excitation filter. The device works with a smartphone or other mobile device to detect plastic particles in a liquid sample. Using customized software with machine-learning algorithms, the tool captures images of the particles as they glow under the green LED light, making them easy to see and measure.

To test the device, Dr. Yang’s team used disposable polystyrene cups. They filled the cups with boiling water and let it cool for 30 minutes. The results were shocking: the cups released hundreds of millions of nano-sized plastic particles, each one about one-hundredth the width of a human hair.

“Once the microscope in the box captures the fluorescent image, the app compares the image’s pixel area with the number of plastic particles,” explained Haoming (Peter) Yang, a master’s student and co-author of the study. “The readout shows whether plastics are present and how much. Each test costs just 1.5 cents.”

Currently, the tool is designed to detect polystyrene, but the software can be adjusted to measure other types of plastics, like polyethylene or polypropylene. The researchers hope to commercialize the device for use in various real-world applications, such as testing food and beverages for plastic contamination.

While scientists are still studying the long-term effects of ingesting plastic particles, the results so far are concerning. Dr. Yang advises people to reduce their plastic intake by avoiding petroleum-based plastic products whenever possible.

Instead, consider using alternatives like glass or stainless steel for food containers. The development of biodegradable packaging materials is also crucial for replacing traditional plastics and creating a more sustainable future.

This new tool could be a game-changer in helping us understand and limit our exposure to microplastics, potentially leading to healthier lives and a cleaner planet.