The amazing Gaia mission to chart stars in the Milky Way Galaxy is also an expert asteroid hunter.

Now, astronomers are reporting its success at spotting more moons of asteroids in our solar system.

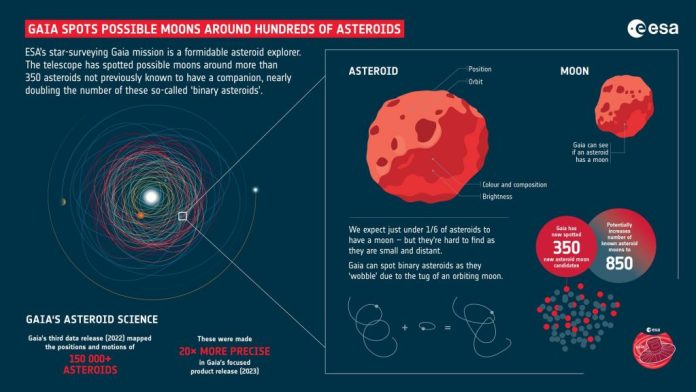

Once the Gaia data from its release 3 are confirmed, those observations will add 352 more binary asteroids to the known count.

That nearly doubles the known number of asteroids with moons and previous Gaia data releases also revealed asteroids in its survey.

The spacecraft’s observations uncovered these possible moons around at least 350 asteroids—making them binary systems. That’s in addition to the known binary asteroids—those objects with companions—that it found with its precise sweeps of the sky.

The most recent discoveries come from “blind” astrometric surveys (not necessarily directed at any one part of the sky or specific objects) and show that the collection of asteroids is more complex than we thought.

“Binary asteroids are difficult to find as they are mostly so small and far away from us,” says Luana Liberato of Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, France, lead author of a new study announcing Gaia’s results.

“Despite us expecting just under one-sixth of asteroids to have a companion, so far we have only found 500 of the million known asteroids to be in binary systems. But this discovery shows that there are many asteroid moons out there just waiting to be found.”

Gaia astrometry for the win

Astrometry used to be thought of as a fairly “boring” part of astronomy. It’s the precision study of the positions of objects in space.

Not quite as exciting as finding new comets or charting new galaxies. Yet, it’s an important branch because, without it, we’d have more difficulty finding things like planets around stars. Those are notoriously difficult (if not impossible) to detect using imaging techniques.

However, a star’s position in space changes thanks to gravitational tugs from its planets. Thanks to precise astronometric measurements made by Gaia and other instruments, astronomers can detect the minute shifts in stellar positions.

It turns out that Gaia’s astrometric abilities are precise enough to detect similar shifts in the positions of asteroids.

For example, in one of its data releases, the spacecraft’s survey pinpointed the positions and motions of more than 150,000 asteroids. Those positions were precise enough that researchers could detect very tiny shifts in their positions over time. Those shifts meant that the asteroids had companions influencing their positions and motions in space.

Not only did the instruments onboard Gaia measure those positions accurately, they also allowed scientists to do “asteroid chemistry”. The data it gathered consisted of spectra of the reflected light from each asteroid.

The spectra show the fingerprints of an asteroid’s surface composition. Future measurements are expected from the spacecraft in the coming years as part of its data release 4.

Why Asteroids?

The Solar System is a collection of objects consisting of one star, multiple planets, moons, rings, comets, and asteroids. Those last two categories sometimes get lumped together as “leftovers of planet formation.”

They are, indeed, the materials that didn’t coalesce into planets and moons. As such, they also contain a lot of information about what conditions were like in the original nebula where the Sun and planets formed.

That includes insight into the distribution of rocky and icy materials. In addition, as we’re seeing with the Gaia measurements, binary asteroids appear to be a normal part of that population of small rocky/icy bodies that exist throughout the Solar System.

Asteroids are sorted into “families” based on their orbits and other characteristics. The largest collection exists in the Asteroid Belt, which lies between Mars and Jupiter.

There are also other collections that orbit the Sun at other distances—such as the near-Earth asteroids. As we see with the discovery of more binary asteroids, not all of these objects orbit alone.

Binaries show us that asteroids can collide after formation, re-coalesce, and interact with each other in space. And, the Gaia mission is showing that performing precise astrometric measurements of objects in our solar system is opening up a new avenue of asteroid studies.

It should help answer the many questions about asteroids, their moons, and the evolution of their orbits.

The future of asteroid moon studies

Future studies of these objects (whether binary or singular) lie with Gaia and other telescope observations.

Those should help settle some theories in the scientific community about how binary asteroids form. At the moment, there are several ideas, including creating rubble piles of material orbiting together after some catastrophic event.

Another theory suggests that asteroids are what’s left after a moon or other body breaks up by collision or gravitational interaction with a larger body. Any fresh insights will depend on more data from Gaia and other studies of these fascinating objects.

So, far from being a boring “bookkeeping” exercise in astronomy, thanks to Gaia, astrometry enables astronomers and planetary scientists to further our knowledge of the solar system and its complex collection of objects.

Written by Carolyn Collins Petersen/Universe Today.