What does it take to have life at another world?

Astrobiologists say you need water, warmth, and something for life to eat. If it’s there, it’ll leave signs of itself in the form of organic molecules called amino acids.

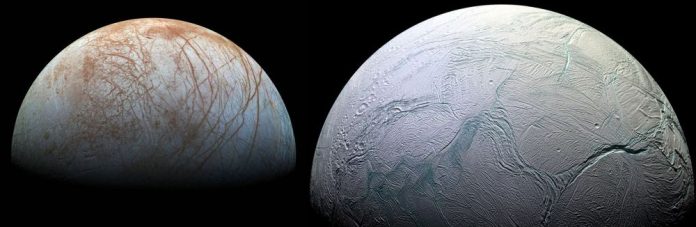

Now, NASA scientists think that those “signatures” of life—or potential life—could exist just under the icy surfaces of Europa and Enceladus.

If future explorations find those signatures, it’ll make a major step in the search for life elsewhere in the Solar System—and beyond. That’s one reason why robotic missions will someday land on those moons—to look for the signs of life.

The next mission to Europa, called Europa Clipper, will orbit that tiny moon, but won’t land. However, it will look for environments suitable for life.

So, that’s a start. There’s also a proposed mission called Enceladus Orbilander. It could launch in 2038 and spend a year checking out that moon.

The Search for Life Signs

Scientists strongly suspect there’s a warmish salty ocean beneath the ices of both Europa and Enceladus.

Moreover, they are probably heated by tidal stresses. So, those are two of the ingredients for life right there. Given what we know about these worlds, there could be something to feed that life, too.

If life does exist, it could “imprint” its existence in the form of amino acids, nucleic acids, and other organic molecules in the surface ice. Life probably wouldn’t exist right on the surface, mostly due to radiation and the lack of atmosphere at those worlds.

That makes the near sub-surface ice a good place to look for evidence of that life. That will require a little digging to find the evidence. How deep? According to Alexander Pavlov of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, it wouldn’t be far.

“Based on our experiments, the ‘safe’ sampling depth for amino acids on Europa is almost 8 inches (around 20 centimeters) at high latitudes of the trailing hemisphere (hemisphere opposite to the direction of Europa’s motion around Jupiter) in the area where the surface hasn’t been disturbed much by meteorite impacts,” Pavlov said.

“Subsurface sampling is not required for the detection of amino acids on Enceladus – these molecules will survive radiolysis (breakdown by radiation) at any location on the Enceladus surface less than a tenth of an inch (under a few millimeters) from the surface.”

Testing that Hypothesis

Of course, scientists don’t have any samples of ice on hand to study from either Europa or Enceladus.

So, Pavlov’s team simulated the conditions to see if rovers and landers could find evidence of organic materials and life on those worlds.

They used amino acids in ice and those from dead microorganisms in radiolysis experiments as possible representatives of biomolecules on icy moons. Radiolysis uses ionizing radiation to bombard molecules and break them apart.

The team mixed samples of amino acids with ice chilled to about -196 Celsius and bombarded them with gamma rays. Since the oceans might host microscopic life, they also tested the survival of amino acids in dead bacteria in ice.

Finally, they tested samples of amino acids in ice mixed with silicate dust. That tested the potential mixing of material from meteorites or the interior with surface ice.

Amino acids are interesting because life can create them. Other non-biological chemistry processes also make them. Scientists studied specific kinds of amino acids that could exist on Europa or Enceladus, particularly those amino acids from the microorganisms they tested (called A. woodii).

If other microorganisms similar to that one existed at Europa or Enceladus, they could be a potential sign of life. That’s because they are used by terrestrial life as a component to build proteins. Those make enzymes that speed up or regulate chemical reactions and make structures.

Moving Evidence of Life to the Icy Surface

If such life did exist on either world’s subsurface oceans, the next question is how its “fingerprint” amino acids get to the ice so close to the top layers of ice. There’s evidence of resurfacing at both worlds by ocean water from below.

On Europa, there are surface units much younger than others, which indicates that water makes its way to the surface and freezes. On Enceladus, geysers shoot material out to space from below the surface.

Amino acids and other compounds from subsurface oceans could be brought to the surface by geyser activity or the slow churning motion of the ice crust.

So, it looks like the team’s experiment shows that amino acids could survive on both worlds, under certain conditions, but they also degrade at different rates. That’s important news for future missions, according to Pavlov.

“Slow rates of amino acid destruction in biological samples under Europa and Enceladus-like surface conditions bolster the case for future life-detection measurements by Europa and Enceladus lander missions,” he said.

“Our results indicate that the rates of potential organic biomolecules’ degradation in silica-rich regions on both Europa and Enceladus are higher than in pure ice and, thus, possible future missions to Europa and Enceladus should be cautious in sampling silica-rich locations on both icy moons.”

Written by Carolyn Collins Petersen/Universe Today.