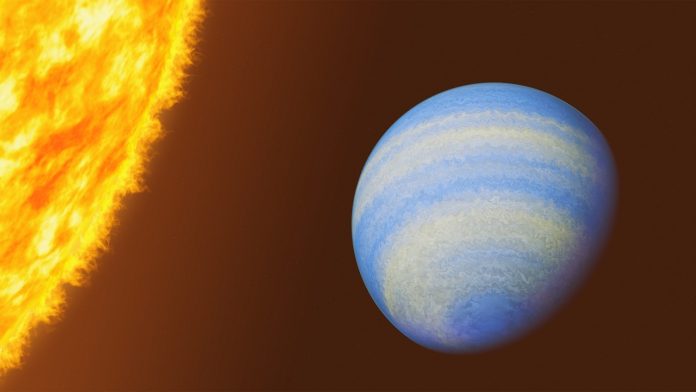

An exoplanet known for its deadly weather has another surprising feature—it smells like rotten eggs!

Scientists using data from the James Webb Space Telescope discovered that the atmosphere of HD 189733 b, a Jupiter-sized gas giant, contains hydrogen sulfide.

This molecule not only has a strong odor but also gives scientists new clues about the composition of distant planets.

“Hydrogen sulfide is a major molecule that we predicted but hadn’t detected outside our solar system until now,” says Guangwei Fu, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University who led the research.

“We’re not looking for life on this planet because it’s too hot, but finding hydrogen sulfide is a step towards understanding how different types of planets form.”

HD 189733 b is about 64 light-years from Earth and is the closest “hot Jupiter” that scientists can study as it passes in front of its star.

Discovered in 2005, this planet has been a key subject for understanding exoplanetary atmospheres.

The planet orbits its star in just two Earth days and is 13 times closer to its star than Mercury is to the Sun. With scorching temperatures around 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit, it has extreme weather, including glass rain and 5,000 mph winds.

In addition to finding hydrogen sulfide, Fu’s team measured the main sources of oxygen and carbon in HD 189733 b’s atmosphere, including water, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide. “Sulfur is essential for building complex molecules,” Fu explains.

“We need to study it more to understand how planets are made and what they’re composed of.”

The James Webb Space Telescope has given scientists a new tool to study these molecules. By observing HD 189733 b, scientists can better understand how sulfur and other elements play a role in planet formation.

“If we study another 100 hot Jupiters and they’re all rich in sulfur, it could change how we think they form compared to our own Jupiter,” Fu says.

The new data also ruled out methane in HD 189733 b’s atmosphere with unprecedented precision, contradicting earlier claims about its abundance. “We thought this planet was too hot for high methane levels, and now we know it doesn’t have much at all,” Fu says.

The team also found heavy metals similar to those on Jupiter. This could help scientists understand how a planet’s metal content relates to its mass. Less massive icy giants like Neptune and Uranus have more metals than gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn. Scientists are investigating whether this pattern holds for exoplanets too.

“This Jupiter-mass planet is close to Earth and has been well studied. Our new measurements confirm that its metal concentrations support our understanding of how planets form,” Fu says. “The findings suggest that planets form by accumulating solid material before being enriched with heavy metals.”

Fu’s team plans to study sulfur in more exoplanets to understand how it influences their formation near their stars.

“We want to know how these kinds of planets got there, and understanding their atmospheric composition will help us answer that question,” Fu says.

The research appears in the journal Nature.