Using modern techniques, researchers have revisited Johannes Kepler’s nearly forgotten sunspot drawings and uncovered new information about solar cycles before the grand solar minimum.

An international team, led by Nagoya University in Japan, recreated the conditions of Kepler’s observations and applied Spörer’s law with modern statistics.

They determined the position of Kepler’s sunspot group, placing it at the end of the solar cycle before the one observed by early telescopic astronomers like Galileo Galilei.

Their findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, help resolve debates about the duration of solar cycles in the early 17th century.

This period marks the transition from regular solar cycles to the grand solar minimum, known as the Maunder Minimum (1645–1715), a prolonged period of low sunspot activity that influences solar activity and its effects on Earth.

Kepler’s important observations

Johannes Kepler, famous for his work in astronomy and mathematics, made one of the earliest recorded observations of solar activity in 1607, before the advent of telescopic sunspot drawings.

Using a camera obscura, an early projection device, he sketched visible features on the sun.

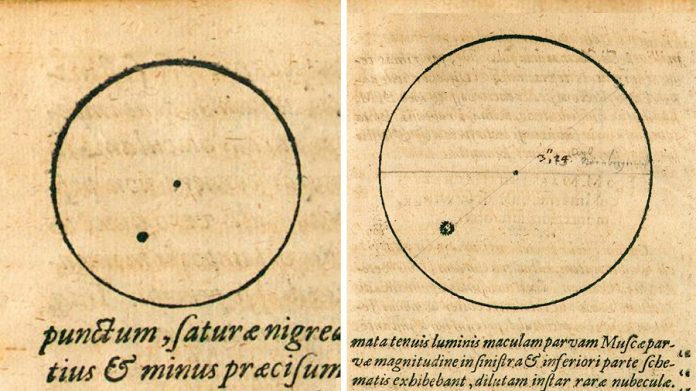

In May 1607, Kepler mistakenly thought he saw a transit of Mercury across the sun, but it was later identified as a group of sunspots. Sunspots are darker areas on the sun’s surface caused by intense magnetic activity and their patterns affect solar radiation and space weather.

Hisashi Hayakawa, the lead author of the study, highlighted the significance of Kepler’s records. “This is the oldest sunspot sketch ever made with an instrumental observation and a projection,” he said.

“We realized that this sunspot drawing could tell us the location of the sunspot and indicate the solar cycle phase in 1607 if we could reconstruct the heliographic coordinates—positions of features on the sun’s surface—at that time.”

Four Key Findings

- Accurate Placement: After adjusting Kepler’s sunspot drawings for the solar position angle, researchers placed the sunspot group at a low heliographic latitude. This contradicts the famous schematic drawing in Kepler’s book, showing the sunspot in the upper left of the solar disk.

- End of Solar Cycle -13: Using Spörer’s law and modern sunspot statistics, the team identified the sunspot group as likely being at the end of solar cycle -13, not the beginning of solar cycle -14.

- Transition Observations: Their findings contrast with later telescopic observations showing sunspots at higher latitudes. This aligns with Spörer’s law, which describes the migration of sunspots from higher to lower latitudes during a solar cycle.

- Cycle Duration: Kepler’s records suggest a regular duration for solar cycle -13, challenging previous reconstructions that proposed extremely short or long cycles during this period.

The 17th century: A key time for astronomy

The 17th century was crucial for solar observation. It was when sunspot observations began and solar activity transitioned from normal cycles to the Maunder Minimum, a unique period of reduced solar activity.

Researchers previously debated whether solar cycles at this time were unusually short or long. Kepler’s observations provide an independent, observational record that helps clarify these debates.

“Kepler’s legacy extends beyond his observational prowess,” Hayakawa explained. “It informs ongoing debates about the transition from regular solar cycles to the Maunder Minimum.” By placing Kepler’s findings within broader solar activity reconstructions, scientists gain crucial context for interpreting changes in solar behavior during this pivotal period.

Sabrina Bechet, a researcher at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, added, “It’s fascinating to see historical figures’ legacy records convey crucial scientific implications to modern scientists centuries later. We still have much to learn from these historical figures. In the case of Kepler, we are standing on the shoulders of a scientific giant.”

Kepler’s sunspot sketches predate existing telescopic sunspot records by several years, serving as a testament to his scientific acumen and perseverance.