It turns out that bacteria, like humans, have memory!

A recent study led by Dr. Ilana Kolodkin-Gal from the Scojen Institute for Synthetic Biology at Reichman University discovered that beneficial bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, have a remarkable ability to remember.

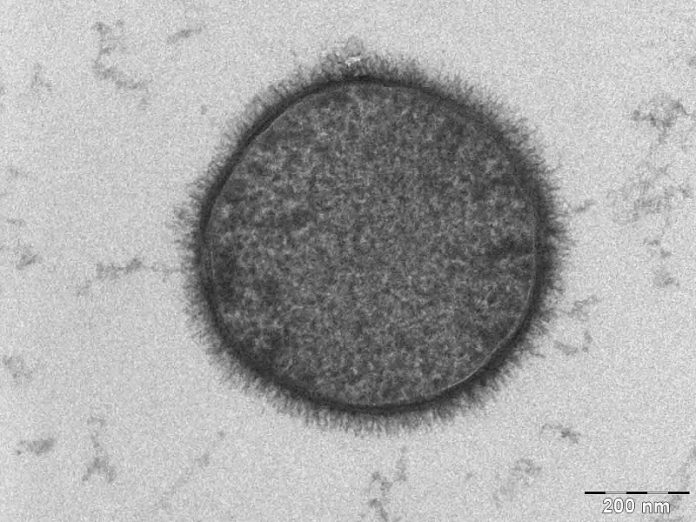

Bacillus subtilis is known for its use as a probiotic and a biological control agent in agriculture.

These bacteria can remember and express genes related to colonization and symbiosis with their host for many generations, even after being separated from the host.

This memory helps the bacteria quickly and efficiently recolonize a new host, giving them an advantage over new bacteria that have never interacted with a plant before.

The study found that the genes with memory, passed down through generations, are linked to stress resistance.

This shows how important the defenses developed during plant colonization are for the bacteria.

This multigenerational memory helps stabilize the relationship between beneficial bacteria and their host.

Researchers believe that similar mechanisms help probiotic bacteria in the human gut, providing long-term protection against diseases.

The study was published in the journal Microbiological Research. It was a collaborative effort involving Jonathan Friedman’s group from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Asaph Aharoni’s group from the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Among the researchers were Dr. Omri Gilhar from the Weizmann Institute of Science and Dr. Liat Rahamim-Ben Navi from the Scojen Institute at Reichman University.

Dr. Ilana Kolodkin-Gal explained, “Our research findings allow us to manipulate these memory genes to create synthetic circuits with memory for agricultural and industrial applications. This can also improve the engineering of probiotic bacteria, which usually live for about 30 minutes. We aim for them to respond to signals for hours or even days.”

This discovery opens up exciting possibilities for improving probiotics and developing new technologies for agriculture.

By understanding and manipulating the memory genes of bacteria, scientists hope to create more effective probiotics that can provide longer-lasting benefits for both plants and humans. This could lead to healthier crops and better treatments for gut health.

In summary, the study shows that bacteria have the ability to remember past interactions with their hosts, which helps them survive and thrive in new environments. This memory can be harnessed to improve probiotics and agricultural practices, providing long-term benefits for health and farming.