While black holes are known as the most destructive objects in the universe, their evolution is largely shrouded in mystery.

This is because while astronomers are familiar with supermassive black holes that exist at the center of galaxies like our own and black holes whose masses are less than 100 times the size of our Sun, the notion of intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) have largely eluded discovery.

However, this might change with the recent discovery of a black hole candidate that could exist within the globular cluster, Omega Centauri, and holds the potential to be the “missing link” in scientists better understanding black hole evolution.

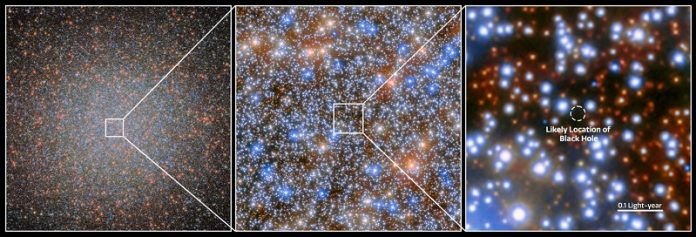

For the discovery, an international team of researchers used the Hubble Space Telescope and spent approximately 20 years examining more than 500 images of seven fast-moving stars that lie within Omega Centauri, which is located just over 17,000 light-years from Earth and estimated to be just over 11.5 billion years old.

A possible reason for the lengthy research time is because Omega Centauri is estimated to contain approximately 10 million stars, each with an average mass of four of our Suns, with the globular cluster being approximately 150 light-years in diameter.

“We discovered seven stars that should not be there,” said Maximilian Häberle, who is a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany and the investigation lead.

“They are moving so fast that they should escape the cluster and never come back. The most likely explanation is that a very massive object is gravitationally pulling on these stars and keeping them close to the center.

The only object that can be so massive is a black hole, with a mass at least 8200 times that of our Sun.”

For context, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy is approximately 4.3 million times the mass of our Sun, which could put this black hole candidate in the “intermediate range” based on what scientists know about smaller black holes being less than 100 times the mass of our Sun.

However, the only other study that suggested the existence of an IMBH within Omega Centauri was in 2008, so this latest discovery will require further examination as the researchers have yet to determine this candidate’s exact mass and position within Omega Centauri.

“This discovery is the most direct evidence so far of an IMBH in Omega Centauri,” said Dr. Nadine Neumayer, who is a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and who began the study.

“This is exciting because there are only very few other black holes known with a similar mass. The black hole in Omega Centauri may be the best example of an IMBH in our cosmic neighborhood.”

This new candidate continues a long list of potential IMBH discoveries dating back to 2004, with no definitive confirmations being made to this day.

Additionally, given this potential IMBH is located just under 17,000 light-years from Earth, if confirmed, could be the closest black hole to Earth, beating out the supermassive black hole residing at the center of our galaxy, which is approximately 27,000 light-years away.

As noted, black holes are known as the most destructive, yet most mysterious, objects in the universe. This is because they can’t be directly observed and are only detectable when they consume an object in their surrounding environment, most often a star.

However, once detected, astronomers can learn much about their behavior, which includes the production of gravitational waves when two black holes merge, as was discovered in 2016.

Additionally, their evolution remains a mystery, as astronomers have debated for decades regarding how black holes form, evolve, and even die. Therefore, confirming the existence of the first IMBH could bring astronomers one step closer to better understanding black hole evolution throughout the universe.

How will IMBHs help astronomers better understand black hole evolution in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!

Written by Laurence Tognetti/Universe Today.