Inside a frame in Roberta and Andre Moore’s den in Pasadena, California, are medals – the kind attached to wide striped ribbons that hang around the necks of athletes, signifying a race completed.

The Moores also have a folder stuffed with numbers once pinned to their workout clothes while they walked various 5Ks during the past several years.

Weekend warriors across the country have similar collections. What makes these race souvenirs unique is that each event they competed in had only three entrants: Roberta, Andre and their daughter, Andrea.

“Andrea is behind all these,” said Andre, who is 73. “She makes 5Ks for us. She’ll say, ‘Let’s go, Mom and Dad,’ and off we go.”

The family knows all too well the importance of exercising and eating right. Three times in the past quarter century, Andre has had heart issues that almost killed him.

The first happened around 2000 when he and Roberta were out for an evening with friends. They enjoyed a steak dinner, which Andre capped off with a cigar.

Then they went to the movies. He began to sweat profusely – “he was drenched,” Roberta said – and couldn’t catch his breath. Roberta called 911. The ambulance took them to the hospital.

Andrea had just turned 23 and was living at home. She was a little concerned her parents weren’t home when she went to bed, but figured their evening just ran late. When they still weren’t there the next morning when she woke up, “I went into full panic.”

Her mother finally called to say her dad had had a heart attack. Andrea rushed to the hospital. When his tests went much longer than expected, she remembers going to the hospital parking lot and praying.

Please, God, she said. Don’t take my dad.

“This was all new to us,” Andrea said. “My dad’s brother had open-heart surgery, but he was a lifetime smoker. He never exercised. My dad only smoked cigars sometimes and was active. This was like a kick in the side.”

Turns out, her father had a blockage. A procedure to insert a stent went well, restoring normal blood flow. Andre was home within a day or two and immediately made lifestyle changes.

He cut out most fast food and began eating fish, brown rice and lots of vegetables. He began walking. He stopped smoking cigars.

Soon, “I was in my best shape ever,” Andre said.

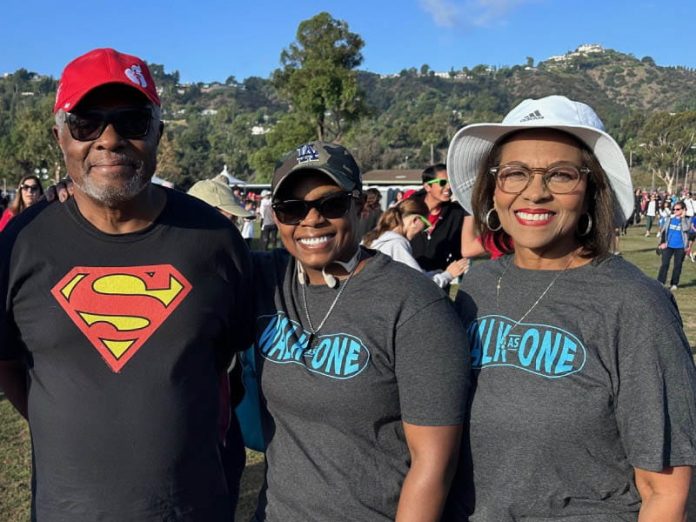

Andre and Roberta Moore earn medals for completing virtual 5Ks entered by their daughter, Andrea. (Photo courtesy of the Moore family)

For 20 years, he had no issues. Then one day in February 2020, he felt woozy and had trouble breathing. He confessed to his wife and daughter that he’d been feeling like that for a few months. Again, Roberta called 911.

At the hospital, doctors suspected the stent had closed – which would have been preferable to what they found: He had blockages in six coronary arteries.

“I was petrified, just praying and praying, ‘Please, God, don’t take my dad,'” Andrea said.

Andre had a bypass procedure, allowing doctors to redirect blood flow around the blocked arteries. The six-hour procedure allowed his heart, which essentially was “starving,” doctors told them, to get the lifesaving blood it needed to keep him alive.

Again, the family worked together to keep their patriarch healthy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mall walking led to outdoor walking through their neighborhood. (Andrea lives half a mile from her parents.) They went on a camping and hiking trip in Utah. Then in February 2023, everything changed again.

“I was pushing myself on the treadmill one day,” Andre said. “At one point, my heart rate was up to 150, 160 beats per minute.”

After that, he remembers nothing. Roberta heard a crash, which turned out to be Andre falling in the bathroom. She rushed in. When she asked if he was OK, he only said, “Don’t tell Andrea I fainted.” Then his eyes rolled back in his head and he lost consciousness.

Roberta did exactly what she needed to do: She called 911, made sure the front door was unlocked for the paramedics, put the dog in the backyard and started giving her husband chest compressions. When the paramedics arrived and took over, she called Andrea.

By the time Andrea got there, which only took a few minutes, the reality of what was happening had hit Roberta. She was on the stairs, sobbing. They could both hear the automated external defibrillator giving directions to paramedics as they worked to save Andre’s life.

After what Andrea said seemed “an eternity,” the paramedics told her and her mother, “We got a heartbeat, but he’s going to have to fight.”

Doctors determined he’d had a cardiac arrest brought on by dehydration. Andre was sedated for almost 48 hours and then slowly started coming back. He began squeezing the hands of his wife and daughter. When the intubation tube was removed and he took those first precious breaths on his own, tears filled his eyes – only one of a few times Andrea has seen her father cry.

He now has an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or ICD, which his cardiologist called “a safety net.” If his heart gets out of whack again, the ICD will give him an electric jolt to restore a normal rhythm.

“The paramedics told me I saved his life,” Roberta said. “I say they saved his life. I don’t take credit for that. He was gone. I give credit to God for taking over.”

More than a year has passed. The family continues to earn Andrea-generated 5K medals, to eat healthy foods, to draw comfort from each other.

“I think we’re closer,” Roberta said. “Seems this trauma has made us pay attention more to how we’re feeling. We check on each other more. Not that we didn’t before, but something can happen so quickly.”

And as for the importance of starting CPR during a cardiac arrest, “those few minutes could be the difference between saving your loved one … or not.”

Written by Leslie Barker.

If you care about heart health, please read studies about top 10 foods for a healthy heart, and how to eat right for heart rhythm disorders.

For more health information, please see recent studies about how to eat your way to cleaner arteries, and salt and heart health: does less really mean more?