Scientists have found patches of water frost on Mars’ tallest volcanoes, known as the Tharsis volcanoes.

This discovery challenges previous ideas about the Martian climate and provides new insights into how water behaves on Mars.

An international team of planetary scientists detected these frost patches on the Tharsis volcanoes, which are the tallest in the solar system.

This is the first time frost has been spotted near Mars’ equator, where temperatures are usually too high for frost to form.

The team published their findings in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Adomas Valantinas, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University, led the study.

He explained, “We thought it was unlikely for frost to form around Mars’ equator because the sunlight and thin atmosphere keep temperatures relatively high.

What we’re seeing might be a remnant of an ancient climate cycle on modern Mars, where there was once precipitation and perhaps snowfall on these volcanoes.”

The frost appears for only a few hours after sunrise before evaporating in the sunlight. It is very thin, about the width of a human hair. Despite its thinness, the frost covers a large area and amounts to at least 150,000 tons of water.

This is equivalent to about 60 Olympic-size swimming pools, cycling between the surface and atmosphere each day during the cold seasons.

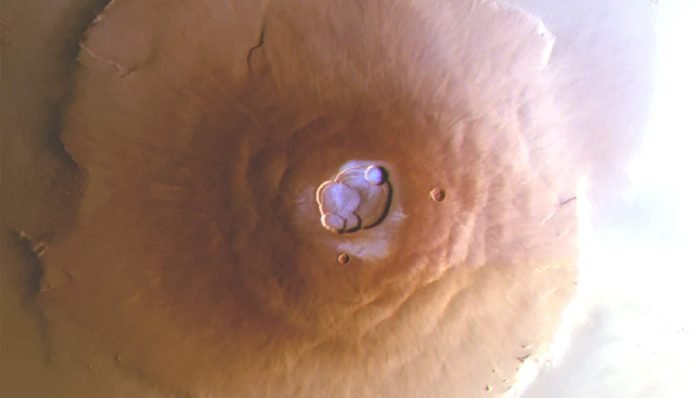

The Tharsis region, where the frost was found, has many volcanoes that are much taller than Earth’s Mount Everest. Olympus Mons, one of these volcanoes, is as wide as France.

The frost is located in the calderas, which are large hollows at the volcanoes’ summits created during past eruptions. The researchers suggest that unique air circulation above these mountains creates a microclimate that allows the frost to form.

Understanding how these frosts form could help scientists learn more about Mars’ water and atmospheric dynamics, which is essential for future exploration and the search for signs of life.

The researchers used high-resolution images from the Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) on the European Space Agency’s Trace Gas Orbiter to detect the frost.

They confirmed their findings using images from other spacecraft, including the Mars Express orbiter and the Nadir and Occultation for Mars Discovery spectrometer.

The team analyzed over 30,000 images to find and confirm the frost. Valantinas began this work in 2018 and completed most of it while earning his Ph.D. abroad, with some reanalysis done at Brown University.

Valantinas now plans to continue exploring Martian mysteries and will focus on astrobiology, studying ancient environments that could have supported microbial life. These samples might one day be brought back to Earth by NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission.

“The idea of life beyond Earth has always fascinated me,” Valantinas said.