In the early 2010s, a startup called LightSquared went bankrupt because its technology interfered with GPS signals.

Now, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania have created a new tool that could prevent such issues in the future.

This new tool is an adjustable filter that stops interference, even in higher-frequency bands, and could enable the next generation of wireless communications.

Troy Olsson, an Associate Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering, led the research. He hopes this filter will pave the way for 6G and beyond.

The electromagnetic spectrum is a valuable resource for wireless communication, but only a tiny part of it is suitable.

Recently, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) made available a new range of frequencies called Frequency Range 3 (FR3), which spans from about 7 GHz to 24 GHz.

Currently, wireless communication mostly uses lower-frequency bands from 600 MHz to 6 GHz, which include 3G, 4G, and 5G.

To handle different frequencies, wireless devices need multiple filters. For example, a smartphone might contain over 100 filters to prevent signals from interfering with each other.

However, this new filter from Penn Engineers can be adjusted to cover a wide range of frequencies, reducing the need for multiple filters.

The challenge with using higher-frequency bands is that many are already occupied by satellites and military communications.

For instance, Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites use some of these bands. The new filter is designed to be adjustable so it can selectively filter different frequencies without needing separate filters.

The secret behind this adjustable filter is a unique material called “yttrium iron garnet” (YIG), a blend of yttrium, iron, and oxygen.

YIG can change frequency when exposed to a magnetic field. By adjusting the magnetic field, the filter can tune to any frequency between 3.4 GHz and 11.1 GHz, covering much of the newly available FR3 band.

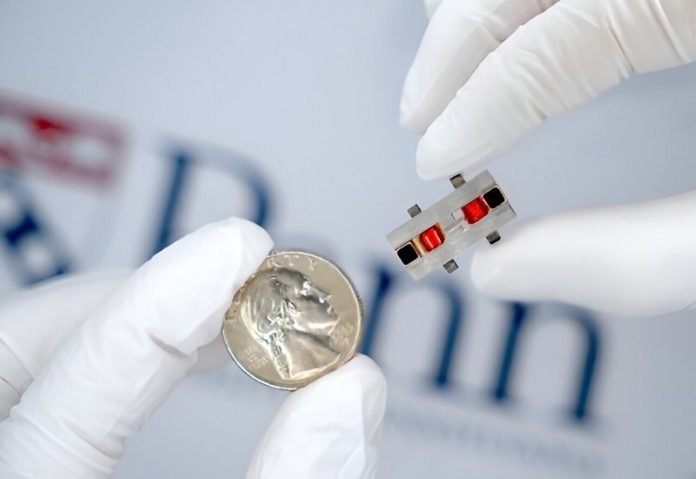

The new filter is also very small, about the size of a quarter, compared to older YIG filters, which were much larger.

This makes it possible to fit the filter into mobile phones in the future. Additionally, the filter uses very little power because of a special circuit that creates a magnetic field without requiring constant energy.

Although YIG was discovered in the 1950s and YIG filters have been around for decades, the combination of the new circuit and extremely thin YIG films has significantly reduced the filter’s power consumption and size. The new filter is ten times smaller than current commercial YIG filters.

Olsson and his team will present their new filter at the 2024 IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques Society International Microwave Symposium in Washington, D.C.

This breakthrough could be crucial for the development of 6G and future wireless technologies, ensuring better performance and less interference.