Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have made a fascinating discovery about tardigrades, tiny creatures known for their extraordinary ability to survive in extreme conditions.

A new study led by Bob Goldstein’s lab and published in the journal Current Biology has revealed that tardigrades have a unique method of repairing radiation damage to their DNA, which could lead to breakthroughs in protecting other forms of life from radiation.

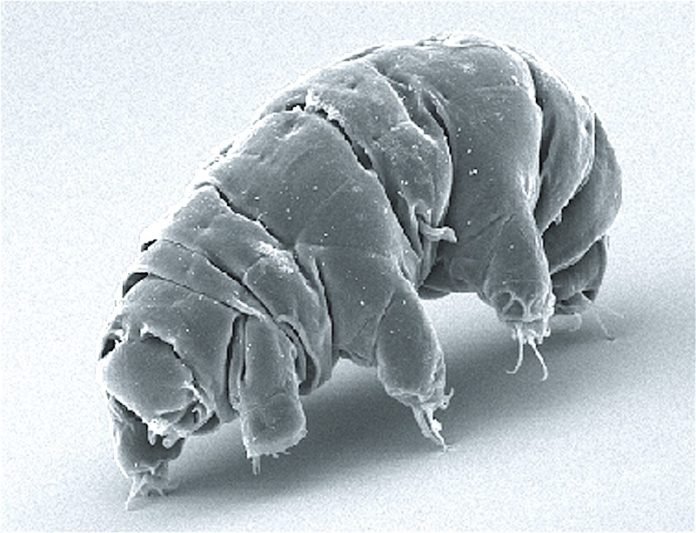

Tardigrades, often called water bears, are microscopic animals famous for their resilience.

They can withstand environments that would be fatal to most other forms of life, including extreme pressures, temperatures, and high levels of radiation.

Previous studies have shown that tardigrades can survive radiation levels up to 1,000 times higher than what would be lethal to humans.

The recent research conducted by Goldstein’s lab at UNC-Chapel Hill, which has been studying tardigrades for over 25 years, focused on how these tiny creatures manage to survive such intense radiation.

They found that tardigrades are not immune to DNA damage caused by radiation but have a remarkable ability to repair this damage.

Courtney Clark-Hachtel, a former postdoctoral scholar in the lab, discovered that tardigrades can significantly increase the activity of genes involved in DNA repair.

These genes produce substances that help fix the radiation-induced damage.

In tardigrades, these substances are produced at such high levels that they are among the most abundant gene products found in any animal.

This robust response to radiation is key to the tardigrades’ incredible survival skills. Clark-Hachtel suggests that understanding how tardigrades repair their DNA under such extreme conditions could lead to new ways to protect other organisms, including humans, from harmful radiation.

In a coincidental discovery, researchers in France from the Museum of Natural History Paris, led by Jean-Paul Concordet and Anne de Cian, found a similar mechanism in tardigrades.

They identified a new protein in tardigrades that helps protect their DNA from radiation damage. These findings were reported in the journal eLife and serve to independently confirm the results of the UNC-Chapel Hill team.

The parallel discoveries of these two research groups highlight the global interest in tardigrades and their unique biology.

By studying these resilient creatures, scientists hope to unlock new methods of safeguarding DNA and enhancing survival in harsh environments.

This research not only deepens our understanding of tardigrades but also opens up potential applications in medicine and biotechnology.