Scientists have come up with a clever way to figure out the temperature of the vast oceans hidden under the icy shells of moons far away from Earth, all without having to actually go there.

This new method, developed by astrobiologists from Cornell University, uses the thickness of a moon’s ice shell to guess how warm the ocean underneath is.

This is a bit like figuring out how warm a cup of coffee is by measuring the thickness of the foam on top, without touching the coffee itself.

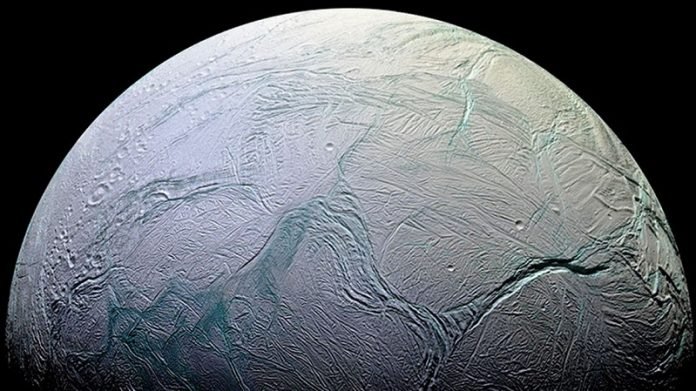

This technique is especially exciting because it can give us a sneak peek into the conditions of oceans on moons like Enceladus around Saturn and Europa, which orbits Jupiter.

These places are interesting to scientists because they might have the right conditions for life as we know it. By understanding the oceans’ temperatures, scientists can learn more about how these mysterious worlds work.

The idea came from observing something called “ice pumping” here on Earth, under the ice shelves in Antarctica. Here’s how it works: when ocean water freezes, it becomes less salty and lighter, causing it to move upwards. As it moves up and the pressure decreases, it freezes again, but this time it forms a different kind of ice. This process can change how the ice looks and feels over time.

In space, around moons like Europa and Enceladus, the same process could happen. By looking at the shapes and slopes of these ice shells from afar, scientists can make educated guesses about what’s happening in the oceans below, including their temperatures. For example, they were able to predict that the ocean on Enceladus might be between minus 1.095 degrees to minus 1.272 degrees Celsius, which is very chilly by Earth standards but quite normal for space!

This finding is a big deal because, until now, there wasn’t really another way to figure out the temperature of these hidden oceans without actually drilling through their ice shells, which is not something we can do yet.

NASA’s mission to Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons, will include a detailed look at its ice shell. This will help scientists use this new technique to learn even more about Europa’s ocean, adding to our understanding of whether this moon could support life.

The research team believes that this method will work well for predicting the conditions on other large moons too, like Ganymede around Jupiter and Titan around Saturn. Each of these moons has its own unique conditions, but the basic idea of using ice shell thickness to learn about ocean temperatures should still apply.

This study shows how research about Earth’s climate and ice can also help us explore and understand other worlds in our solar system. It’s a reminder of how connected our planet is to the broader universe and how studying one can help us learn more about the other.

In simple terms, this new method opens up a whole new way of exploring the hidden oceans of distant moons, helping us to solve the mysteries of these fascinating worlds from millions of miles away.

It’s like being a detective with a telescope, uncovering clues about the possibility of life in outer space.