In a groundbreaking effort to rethink how we test the toughness of materials, researchers from Duke University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are leading the charge towards a major scientific breakthrough.

At the center of this initiative are John Dolbow, a professor specializing in the mechanics of materials at Duke University, and Oscar Lopez-Pamies, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Illinois.

Together, they’re digging deep into the science of fractures to help us better understand and predict when materials will break.

Their work, recently published in a prestigious scientific journal, focuses on improving a longstanding method used to assess the strength of brittle materials – substances that can break easily under stress, which are crucial in industries ranging from construction to medicine.

The story begins in the mid-20th century with Fernando L.L.B. “Lobo” Carneiro, a brilliant engineer who devised the “Brazilian test” while trying to solve a unique problem in Rio de Janeiro.

The city needed to relocate a church sitting at a critical intersection without destroying it.

Carneiro’s innovative solution involved moving the church on concrete rollers, but he needed to ensure these rollers were strong enough for the task.

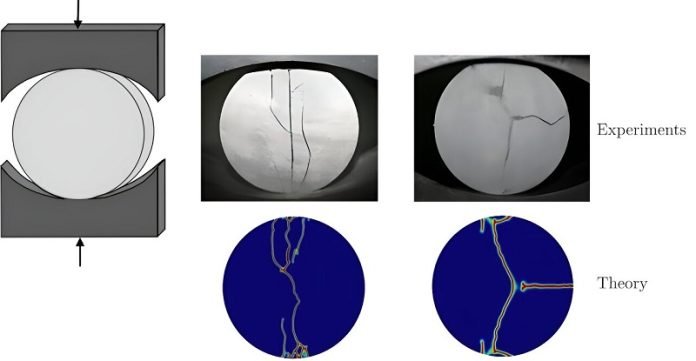

In his experiments, Carneiro discovered that when concrete disks were squeezed, they would crack perfectly in the middle. This accidental discovery led to a simple yet effective test for measuring the tension strength of materials like concrete, which has been widely used for decades.

However, despite its long-standing use, the Brazilian test has been the subject of much debate and scrutiny.

Critics argue that the test’s original formula, which calculates the strength of a material based on the force it can withstand before breaking, oversimplifies how materials fracture.

They suggest that failures often occur in ways that the test does not accurately account for, leading to potential inaccuracies in measuring material strength.

Dolbow and Lopez-Pamies’s research addresses these concerns head-on.

They argue that the conventional approach fails to consider the complex ways in which materials crack under pressure, focusing too narrowly on tension without accounting for other forces at play.

Their insights have led them to propose a modified formula that promises to offer a more accurate assessment of material toughness, which could have significant implications across several fields.

One interesting application of their work is in the medical procedure known as lithotripsy, which uses shock waves to break kidney stones into smaller, passable pieces.

The researchers use a material called BegoStone in their experiments, chosen for its similarity to kidney stones, to better understand the mechanics of material failure.

Their findings suggest that the traditional Brazilian test might not fully capture the intricacies of how materials fracture, particularly in cases where tension and compression forces interact.

By revising the Brazilian test’s formula, Dolbow and Lopez-Pamies aim to improve our ability to gauge material strength accurately, impacting how materials are selected and utilized in everything from building skyscrapers to developing medical treatments.

This breakthrough not only promises to refine an age-old testing method but also challenges established norms, paving the way for innovative engineering practices that could revolutionize our approach to dealing with material fractures.