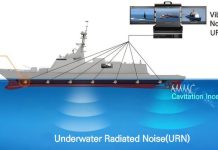

Imagine a bustling city street, with skyscrapers towering above, creating what’s known as an urban canyon.

These areas can get really hot and stuffy, especially in the summer.

Now, researchers from Princeton’s engineering school have found a clever way to bring in more fresh air, using a special kind of lid over spaces like pop-up restaurants and bus shelters.

This isn’t just any lid; it’s inspired by kirigami, the Japanese art of cutting and folding paper, which might just be the solution to making our cities cooler and more comfortable.

The idea is pretty simple at its core.

By designing a cover with slats (called louvers) that tilt, the researchers discovered they could significantly increase airflow through a box, mimicking structures in an urban setting.

This means wind that would usually just skim over the top can now be directed into the space, making it less stuffy and more ventilated.

Taking inspiration from kirigami, the team added a creative twist.

By cutting and stretching the lid in a specific pattern, they transformed it into a 3D shape that can guide air in and out more effectively than if there were no cover at all.

This method was initially explored to improve the air quality and comfort of the small, temporary venues that popped up during the COVID pandemic, which often had poor ventilation when their windows were closed.

Elie Bou-Zeid, a leading researcher on the project, pointed out that their approach could change the way we think about ventilation in tight urban spaces.

By adjusting the roof’s design, they could create a more pleasant environment inside, eliminating the stuffy air that often gets trapped in such enclosures.

But it’s not just about comfort. Bou-Zeid’s work also addresses how cities, with their concrete buildings and paved roads, can become incredibly hot during warmer months.

This phenomenon, known as the urban heat island effect, makes summer in the city a sweltering experience. The kirigami-inspired ventilation could provide a much-needed cooling effect.

The team, including experts in adaptive construction materials and fluid dynamics, started with a traditional approach, using a uniform row of tilting boards.

They then experimented with altering the size, geometry, and orientation of these louvers to maximize airflow.

What they ended up with was a design that varied in board orientation, creating a more dynamic airflow pattern.

Their most innovative step involved using kirigami to reshape the louvers entirely. They crafted a pattern that, when stretched over the box, formed waves that helped guide the air through more efficiently, almost like a honeycomb structure.

This approach was refined through a combination of wind tunnel experiments and computer simulations, allowing the researchers to fine-tune their designs for the best airflow.

Lucia Stein-Montalvo, the project’s lead postdoctoral researcher, emphasized that this study lays the groundwork for applying kirigami-inspired designs in real-world settings.

The next steps involve exploring more realistic scenarios, like those urban canyons, and considering materials and structures that can withstand the demands of city life.

This research opens up exciting possibilities for making our cities cooler and more breathable, proving that sometimes, the best solutions come from combining age-old art forms with modern science.