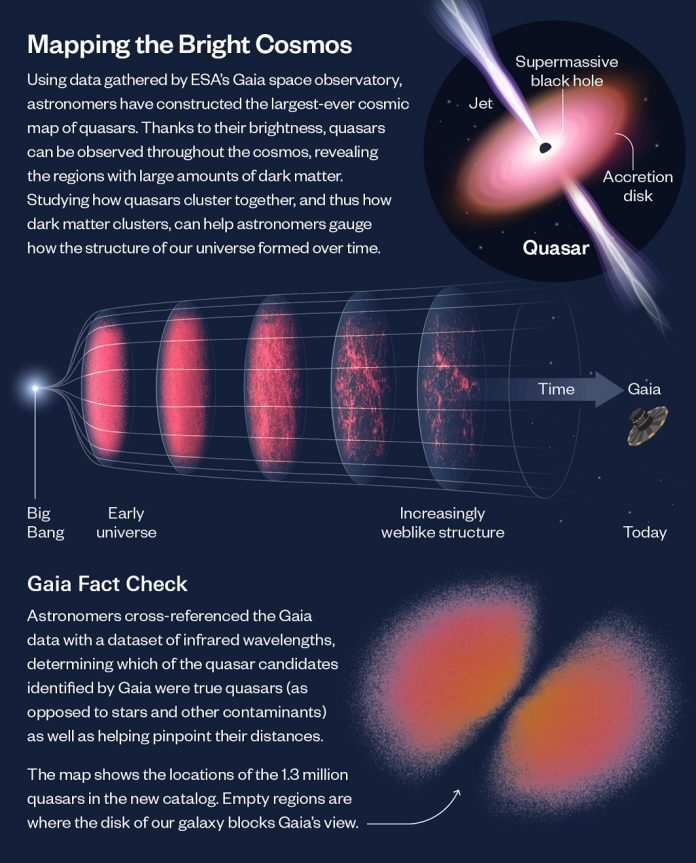

Astronomers have accomplished a massive feat by creating the biggest map yet of the universe.

This isn’t just any map; it’s a detailed chart of around 1.3 million quasars. Quasars are incredibly bright spots in the sky, powered by supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies.

Despite their dark nature, they are among the brightest objects in the universe because they consume gas from their surroundings in a spectacular display of light.

The new map captures quasars that are spread across the universe, some of which are so distant that their light comes from a time when the universe was just 1.5 billion years old—nearly 12 billion years ago!

The universe today is about 13.7 billion years old, so these quasars give us a glimpse into the cosmos’ distant past.

David Hogg, a leading scientist behind the map, explains that this quasar map is unique because it covers the largest area of the universe ever mapped in this way.

While there are other catalogs with more quasars or better measurements, none match the sheer volume of the universe this one encompasses.

The map was made using data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope, which primarily aims to map stars in our own galaxy.

However, as Gaia scans the sky, it also captures images of objects far beyond, including quasars and other galaxies.

This “bonus” data from Gaia helped the researchers make precise measurements of the early universe’s structure.

Quasars are fascinating not just for their brightness but also for what they can teach us about the cosmos.

They are found in galaxies surrounded by dark matter, a mysterious substance that doesn’t emit light but has a gravitational pull. By studying quasars, astronomers can learn more about dark matter and how it clusters.

Additionally, the location of quasars and their host galaxies helps scientists understand how the universe has expanded over time.

They’ve even compared the quasar map with the cosmic microwave background—the oldest light in the universe—to study the cosmic web of dark matter.

The quasar catalog has sparked a wave of new scientific research, from studying the universe’s first moments to mapping cosmic voids and even tracking the motion of our solar system.

This quasar map is a shining example of how astronomy projects can yield unexpected and valuable insights.

Originally intended to map stars in the Milky Way, the Gaia telescope has provided astronomers with a treasure trove of data, offering a glimpse into the entire universe.