Imagine a young star, much like our own sun, but in its earliest days. Around it, there’s a swirling dance of dust and gas. This cosmic ballet doesn’t just make for a pretty picture; it’s the birthplace of planets.

This stage of a star’s life, featuring what’s known as a protoplanetary disk, is crucial to understanding how planets like Earth come to be.

Despite the vastness of space and the countless stars, spotting a planet in the making is extremely rare. So far, astronomers have only managed to catch a glimpse of this process twice. But with the help of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists are hoping to change that.

They’re using JWST’s advanced instruments to peek into these dusty disks with unprecedented clarity, aiming to uncover the secrets of planet formation and how these emerging planets shape their surroundings.

Teams from the University of Michigan, University of Arizona, and University of Victoria have joined forces, combining new images from JWST with previous snapshots taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and the ALMA observatory in Chile.

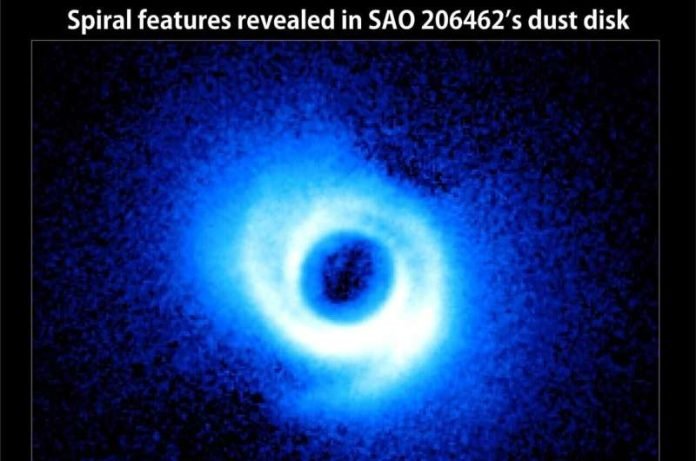

Their goal? To study three specific disks, known as HL Tau, SAO 206462, and MWC 758, with the hope of finding new planets in the act of forming.

One part of the research focused on a disk surrounding a young star called SAO 206462. Here, the scientists thought they might have spotted a new planet being born. However, it wasn’t the large, bright planet they were expecting based on their simulations.

Instead, they found something else, possibly a planet, but they’re not entirely sure yet. It could also be a distant star or galaxy accidentally captured in their observations. Further studies are needed to figure out exactly what they’ve seen.

The intrigue doesn’t stop there. Past observations of SAO 206462 showed two spiral arms in the disk, likely carved out by a planet in formation. Yet, finding this planet is challenging because it’s hidden by the bright glare of the star it orbits, making it incredibly difficult to see.

To overcome this, the researchers used JWST’s NIRCam instrument, which is capable of seeing in infrared light. This allows them to look for the warmth of a planet and signs of materials falling onto the planet at high speeds, a process which emits light at very specific colors.

Another part of the study looked at the youngest system in their survey, HL Tau, surrounded by a thick cloud of dust and gas. The details JWST revealed were stunning, yet this same dust cloud also hides any potential planets from view.

The final piece of their puzzle involved the disk around MWC 758, known for its spiral arms suggesting the presence of a massive planet. Despite the high hopes, no new planets were spotted here either.

This absence of detection across all three systems hints that any planets influencing these disks might be too small, too cold, or hidden by dust to be seen with even the most advanced telescopes.

This research is more than just a cosmic treasure hunt; it’s a fundamental quest to understand the origins of planets, including those that might host life. By studying these protoplanetary disks, scientists hope to piece together the story of how gas giants like Jupiter form and how they might affect the development of smaller, rocky planets.

Every observation, every hint of a planet forming, brings astronomers closer to understanding the cosmic recipe for planet creation. It’s a challenging journey, filled with more questions than answers, but one that could eventually help us understand not just where planets come from, but how our own Earth came to be.

The research findings can be found in The Astronomical Journal.

Copyright © 2024 Knowridge Science Report. All rights reserved.