Astronomers have made a startling discovery about young, distant galaxies: their central black holes are much bigger than we ever thought.

This finding, made possible by the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), is shaking up our understanding of how galaxies and their massive black holes evolve together.

In galaxies like ours, the Milky Way, the stars outweigh the central black hole by a thousand times or more.

But in these newly observed young galaxies, the black holes can be as heavy as the total mass of all the stars in the galaxy. This is a huge difference compared to what we see in older, nearby galaxies.

The JWST, NASA’s newest space telescope, has allowed astronomers to study these young galaxies in ways they couldn’t before.

Previously, they could only observe very bright quasars, which are active black holes that outshine all the stars in their galaxy. But now, with JWST, scientists can see smaller black holes and the stars around them in distant galaxies.

Fabio Pacucci, a researcher at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, led this new study.

He points out that these early black holes are much heavier compared to the stars in their galaxies than what we see in closer, older galaxies. This observation was reported in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and presented at a major astronomy meeting.

Roberto Maiolino, a co-author and professor at the University of Cambridge, explains that these findings challenge our previous understanding of the relationship between a galaxy’s stars and its central black hole.

With the JWST, researchers can now hunt for even smaller and farther black holes, which they believe are quite common.

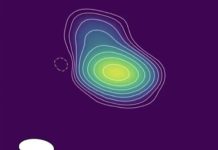

The team studied 21 galaxies, located about 12 to 13 billion light-years away, using data from three JWST surveys.

The black holes in these galaxies are tens or hundreds of millions of times more massive than our sun. They’re smaller than the black holes in distant quasars, but still incredibly huge.

Xiaohui Fan, another co-author and professor at the University of Arizona, notes that the ratio of star mass to black hole mass in these early galaxies was much lower billions of years ago than it is today. This finding is crucial for understanding the first population of black holes.

Scientists think these massive early black holes started from “seeds.” Light seeds would be remnants of the universe’s first giant stars, weighing about 100 to 1,000 times our sun’s mass.

Heavy seeds, on the other hand, would start out much larger, at 10,000 to 100,000 solar masses, formed from huge gas clouds collapsing under gravity. The discovery of these oversized early black holes supports the heavy seed theory, suggesting these black holes started big and grew from there.

But many questions remain.

How did these galaxies and their black holes evolve? Did the black holes grow by pulling in gas or merging with other black holes? And how did the galaxies build up their stars? More studies with JWST will help answer these questions.

Over time, as galaxies and their black holes grow and merge with others, they reach the balance we see in galaxies like the Milky Way.

The researchers are excited to use the JWST to dig deeper into the universe’s past and unravel the story of how it all began.

Source: KSR.