NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has made a groundbreaking discovery in the world of astronomy.

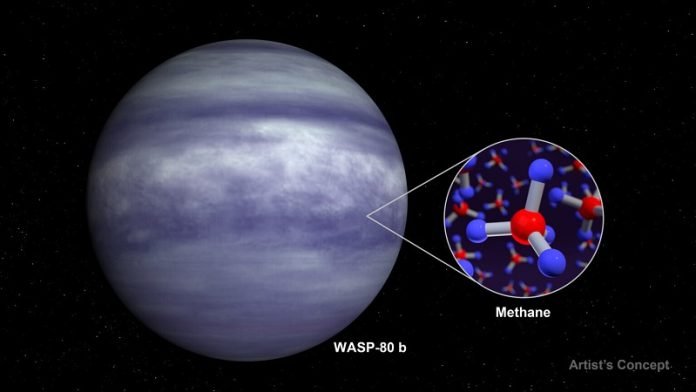

It has detected methane in the atmosphere of an exoplanet named WASP-80 b, a discovery that marks a significant milestone in space exploration and understanding of distant worlds.

The Discovery of Methane on WASP-80 b

WASP-80 b is an exoplanet located 163 light-years away in the constellation Aquila.

It’s a type of planet known as a ‘warm Jupiter,’ similar in size and mass to our Jupiter but much hotter.

Unlike hot Jupiters with extremely high temperatures and cold Jupiters like our own, warm Jupiters have moderate temperatures. WASP-80 b, for example, has a temperature of about 825 Kelvin (about 1,025 degrees Fahrenheit).

This planet orbits its star, a red dwarf, once every three days, which is incredibly fast compared to Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Because of the immense distance and the planet’s proximity to its star, we can’t see WASP-80 b directly, even with advanced telescopes like Webb. Instead, scientists use special methods to study it.

How Scientists Study Exoplanets

To understand what’s happening on WASP-80 b, researchers use two methods: the transit method and the eclipse method.

The transit method involves observing the planet as it moves in front of its star, slightly dimming the starlight, similar to someone walking in front of a lamp. By studying how the light dims, scientists can tell what molecules are in the planet’s atmosphere.

The eclipse method, on the other hand, involves watching the planet as it passes behind its star. This helps scientists measure the light the planet itself emits, which changes depending on the molecules in its atmosphere.

Methane is a critical molecule in understanding planets. It’s abundant in the atmospheres of gas giants in our solar system, like Jupiter and Saturn, but finding it in exoplanets has been challenging until now.

Detecting methane in WASP-80 b’s atmosphere is exciting because it helps us compare planets in our solar system with those far away.

The observations made by the Webb Telescope had to be transformed into something called a spectrum.

This shows how much light is blocked or emitted by the planet’s atmosphere at different colors or wavelengths of light. Scientists used two approaches to ensure their findings were accurate and robust.

To interpret these spectra, researchers used two types of models. The first type tried many combinations of methane and water levels and temperatures to find the best match for the data.

The second type used known physics and chemistry to predict what should be in the planet’s atmosphere. Both models agreed: methane was definitely present.

To be sure their discovery was accurate, scientists used a robust statistical method. They aimed for a 5-sigma detection, which means the odds of the finding being a fluke are 1 in 1.7 million.

Their detection of methane was even more reliable, at 6.1-sigma, making the odds of a mistake only 1 in 942 million.

This discovery is more than just finding a gas; it helps us understand how planets form. By measuring the amounts of methane and water, scientists can infer the ratio of carbon to oxygen atoms.

This ratio changes depending on where and when a planet forms in its system, offering clues about its history.

With this discovery, scientists can now start comparing exoplanets to the planets in our solar system. It opens the door to understanding if the expectations based on our solar system match up with what’s found outside of it.

The James Webb Space Telescope is poised for more exciting findings. Future observations of WASP-80 b could reveal other molecules like carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, giving a fuller picture of the planet’s atmosphere.

As Webb continues to observe exoplanets, our understanding of the chemistry and physics of these distant worlds will deepen, potentially leading to discoveries about planets similar to Earth.

In summary, the detection of methane on WASP-80 b by the Webb Telescope is a significant step forward in space exploration, opening new avenues for understanding distant worlds and their formation.