There’s a big shake-up happening in the world of space science.

A group of smart folks at Northwestern University, backed by the U.S. National Science Foundation, have been busy studying black holes, and they’ve found something really surprising.

They’ve shared their discovery in The Astrophysical Journal, and it’s all about how supermassive black holes eat—and they’re way hungrier than we ever imagined.

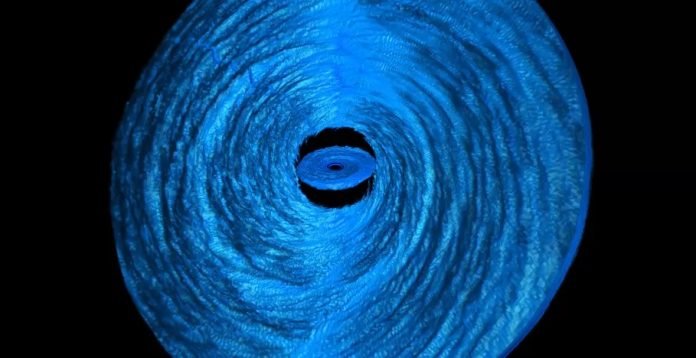

You see, black holes are these incredible, mysterious spots in space where gravity is so strong, even light can’t escape from them. And they eat, or ‘feed,’ by pulling in gas and other materials from their surroundings, which forms a swirling whirlpool called an accretion disk.

For the longest time, scientists thought black holes had pretty slow appetites, munching on their space meals at a leisurely pace.

But these new simulations—super detailed 3D ones, like a space video game that’s super realistic—show that black holes can actually twist and tear up space itself. This action breaks their accretion disk into pieces, making an inner and an outer ring.

First, the black hole chows down on the inner ring. Then, as if it’s not full yet, it grabs the bits and pieces from the outer ring that fall into the empty space it just made.

And this isn’t a slow process; it happens really fast, taking just a few months for a full cycle. Before this, everyone thought it took hundreds of years for a black hole to finish a meal!

This speedy snacking might be the key to understanding why some super bright spots in the sky, like quasars (which are like cosmic lighthouses made by black holes), suddenly flare up and then disappear. It’s been a puzzle because these quasars can change their brightness really quickly, and no one knew why.

Nick Kaaz from Northwestern, who’s the brains behind the study, said that what they used to think about how these disks change over time doesn’t match up with these sudden light show fireworks. The team thinks that the part of the disk that shines the brightest gets wrecked and then rebuilds itself.

Alexander Tchekhovskoy, another scientist in the study, points out that accretion disks are tricky to figure out because they’re just so complex.

And until now, models of how they worked were kind of neat and tidy—gas and particles peacefully swirling around the black hole, all on the same level and direction of the black hole’s own spin.

But in reality, it looks like the area around black holes is actually way messier and more chaotic.

The old idea was that gas would slowly dance its way into the black hole over a super long time, like hundreds or even thousands of years. But this new high-resolution simulation tells us that things are a lot more turbulent and hectic than that.

So, in space terms, black holes might be more like a cosmic food processor on high speed rather than a slow cooker.

And understanding this fast feeding frenzy could help us solve some of the biggest mysteries about the brightest beacons in the night sky.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.