Water is a basic need that we all share. We drink it, cook with it, and bathe in it, trusting that it’s safe for our families and us.

But what if the water coming out of our taps isn’t as clean as we believe it to be?

A team of scientists from across America, led by Professor Johnnye Lewis from the University of New Mexico, has shared startling findings about the water we use daily.

The researchers delved deep into the quality of water from various sources, including public systems and wells, and found some worrying details: many water sources contain dangerous substances that might pose a risk to our health.

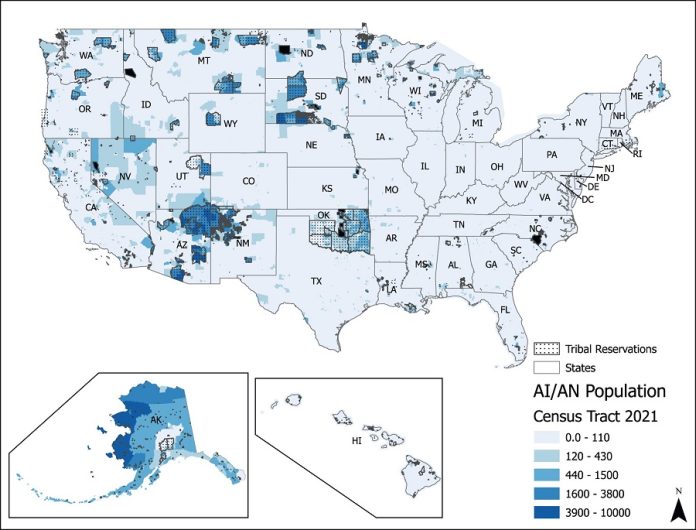

The problems appear to be more pronounced in certain areas, particularly tribal lands and minority communities, and things may get even worse due to the challenges brought by climate change.

The unseen invaders in our water

Through rigorous research, the scientists identified seven contaminants often found in drinking water: arsenic, fracking fluids, lead, nitrates, chlorinated disinfection byproducts, PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), and uranium.

Some of these, like arsenic, uranium, and nitrates, are even common in groundwater – which is alarming because several of these substances have connections to severe health issues like cancer and developmental problems in children.

PFAS, for example, don’t break down naturally and can remain in the environment for a very long time, potentially accumulating and posing ongoing risks.

Our varied risks and challenges

Even more worryingly, these seven contaminants are only the tip of the iceberg.

There are thousands more substances in our water, and our understanding of their effects, especially when combined, is still developing.

The research team emphasizes that contaminants might interact in a mixture, and these mixtures might act differently in various communities, creating a complex challenge for scientists and policymakers trying to ensure safe water for all.

Moreover, the risks aren’t evenly distributed: our smaller community water systems, especially those serving fewer than 10,000 people, may lack the advanced technology to effectively remove or reduce these dangerous substances from their water supply.

This means that a significant number of Americans – 52 million, in fact – may have insufficient protection against these waterborne risks.

Climate change: a rising tide of concerns

As if the present situation wasn’t challenging enough, the future may hold even graver difficulties.

Climate change is already making it harder to locate clean, safe sources of drinking water, particularly in the western U.S., where drought and other water stress are becoming more common.

The effects of climate change will be particularly harsh for those who are already in vulnerable situations, including underserved and minority communities, warns Lewis.

What needs to be done

The researchers’ findings are a wake-up call, highlighting the urgency of upgrading the U.S.’s drinking water infrastructure.

There’s a need for concerted efforts to strengthen drinking water standards, implement better water treatment technologies, and conduct thorough chemical safety testing to safeguard our water.

Additionally, sharing monitoring data transparently and disseminating this information among the public is vital to keep everyone informed about the water they consume.

Professor Lewis and her colleagues believe that, while the challenges are formidable, a collective, determined effort can mitigate the risks and ensure clean, safe drinking water for all Americans.

This will necessitate strong cooperation, significant investment, and focused policy-making, embracing the responsibility to protect one of our most vital resources: our water.

Through a comprehensive approach that encompasses upgraded infrastructure, enhanced regulations, improved treatments, and stringent testing, a future with safer, cleaner water can be realized.

It’s a journey that demands our attention and action, ensuring that every drop of water we consume is free from harm and sustains our health and life.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.

Source: University of New Mexico.