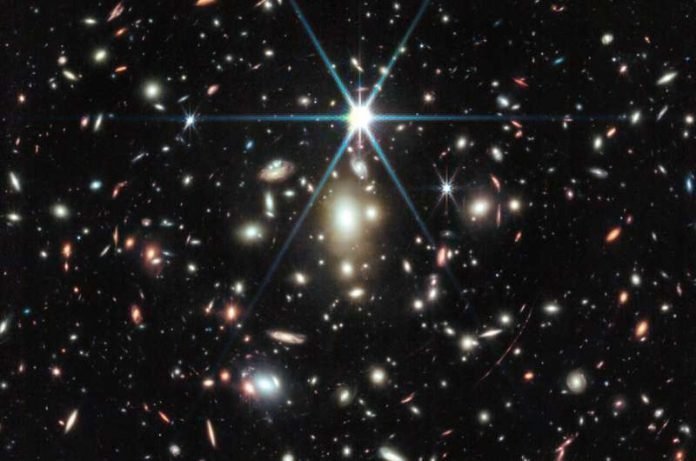

We have a big telescope called the Hubble. For a long time, Hubble was the best at looking at far-off things in space.

In 2022, Hubble found a star that was shining a very, very long time ago, closer to the time of the big bang. We gave this star a fun name: Earendel.

But the Hubble can only do so much. To learn more about Earendel, we needed an even bigger and better telescope.

NASA has another amazing telescope called the James Webb Space Telescope, or just Webb for short. Webb can see things that even the Hubble can’t. So, when Hubble found Earendel, Webb took a closer look.

A Star That’s Different

When Webb looked at Earendel, it found out some fun facts. Earendel is not like our sun. It’s way hotter and shines much brighter. Imagine a light bulb.

Our sun might be like a 40-watt bulb, but Earendel is like a million-watt bulb! And it’s not alone. Webb thinks Earendel might have a buddy star that’s a bit cooler.

Think of it as having a big bright bulb and a smaller, dimmer one right next to it.

But wait, how could we see such an old star? Space is vast, and this star is very far away. It’s like trying to see a tiny ant from the other side of a huge field.

Here’s the trick: there’s something big and heavy (a cluster of galaxies) between us and Earendel. This big cluster acts like a magnifying glass.

When we look through this “space magnifying glass”, Earendel appears bigger and brighter to us.

So, when we look at Earendel, we’re not just seeing an old star. We’re seeing a glimpse of what the universe was like a billion years after it started. That’s a long, long time ago!

More Than Just One Star

Webb did more than just look at Earendel. It saw the whole neighborhood around it. And this neighborhood is a galaxy we call the Sunrise Arc.

In this galaxy, there are places where new stars are being born, and there are older groups of stars hanging out together.

This is a bit like looking at a city from the sky. From up high, you can see both new buildings being constructed and old neighborhoods that have been around for a while.

And just like in a city, these stars tell us stories about their past. Looking at the Sunrise Arc, scientists can imagine what places in our own Milky Way might have looked like when they were young.

Now, Earendel isn’t the only old star we’ve seen. Before Earendel, Hubble had spotted another ancient star, but it wasn’t as old. And since finding Earendel, Webb has seen other ancient stars, too.

None are as old as Earendel, but they are still very, very old. These stars are like grandpas and grandmas, telling stories about what the universe was like when they were young.

Why Does This Matter?

Why should we care about an old star? Because by looking at stars like Earendel, we can learn about our universe’s history. Think of it like a family album.

When you flip through the pages, you can see photos of your grandparents and even your great-grandparents. These photos tell you a bit about what life was like before you were born.

Earendel and stars like it are the universe’s family album. They show us what things were like a very long time ago. By studying them, we can understand how stars are born, how they live, and how they end their lives.

And here’s something even cooler: the big bang was a giant explosion that started our universe. After that explosion, there were only two things: hydrogen and helium.

Scientists dream of finding stars made only from these two things. These would be the very first stars ever. Earendel isn’t one of those stars, but by studying it, we might get one step closer to finding one.

In the end, looking at the sky isn’t just about stars and space. It’s about stories. Every star, every galaxy, has a tale to tell.

And with telescopes like Hubble and Webb, we get to hear these stories and learn about where we come from.

The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.