Have you ever wondered what happens to a star that gets too close to a black hole? Astronomers from the University of Michigan have given us some clues.

They’ve been like cosmic detectives, studying the remains of a star that was torn apart by a supermassive black hole.

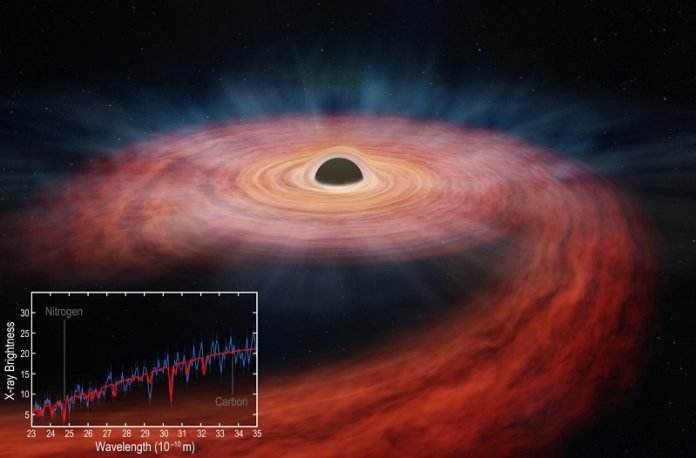

Using special telescopes in space, like NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the team looked at the stuff floating around the black hole.

This stuff wasn’t just random; it used to be the insides of a star! As the star got too close to the black hole, it was shredded to bits, and some of these bits ended up floating in space.

The study has been published in a journal called The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Jon Miller, the lead researcher, said, “We are seeing the guts of what used to be a star.” By examining what’s left, scientists can figure out what kind of star it was before it met its explosive end.

There have been many cases where stars get destroyed by black holes. These events are called “tidal disruption events.”

When a star is torn apart, it causes a bright flash of light that can be seen from Earth. One such event, named ASASSN-14li, is special for a few reasons.

Firstly, when this event was discovered back in 2014, it was the closest one of its kind to Earth in about ten years.

This closeness allowed scientists to get a detailed look at what happened. Using new methods, Miller’s team estimated the amounts of different elements like nitrogen and carbon around the black hole. They found that the destroyed star was probably quite big, about three times the mass of our Sun.

Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, another scientist in the study, said that figuring out the mass of the star that was destroyed is a big deal. “Observing the destruction of a massive star by a supermassive black hole is spellbinding,” he said. Usually, smaller stars are more common, so finding a bigger star like this is rare and interesting.

This study is a big step forward. It confirms that the elements seen near the black hole actually came from a star, not just gas from previous activities of the black hole. Earlier studies were not so clear-cut. For example, a study in 2017 suggested the destroyed star was much smaller.

What does this all mean for the future? Well, knowing the size of a star that gets destroyed can help scientists understand more about the stars that are closest to supermassive black holes in other galaxies. This could reveal new details about the universe, like whether clusters of stars hang around black holes.

Jon Miller also pointed out that this area of research offers great opportunities for students to contribute. Sol Bin Yun, a senior student at the University of Michigan, was among the co-authors of the study.

So the next time you look up at the stars, remember that our universe is a dynamic and sometimes violent place, full of mysteries that scientists are working hard to solve.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.