Ever seen pictures of our Milky Way galaxy?

It’s full of beautiful spiraling arms packed with stars that extend out from the center.

Interestingly, similar patterns have been seen around young stars, where new planets are being born.

These rings of gas and dust, known as protoplanetary disks, give us clues about what our solar system might have looked like when it was just a baby, and they help us understand how planets are formed.

For a long time, scientists believed that the spiral arms in these disks might be created by newly forming planets, but they had no solid proof – until now.

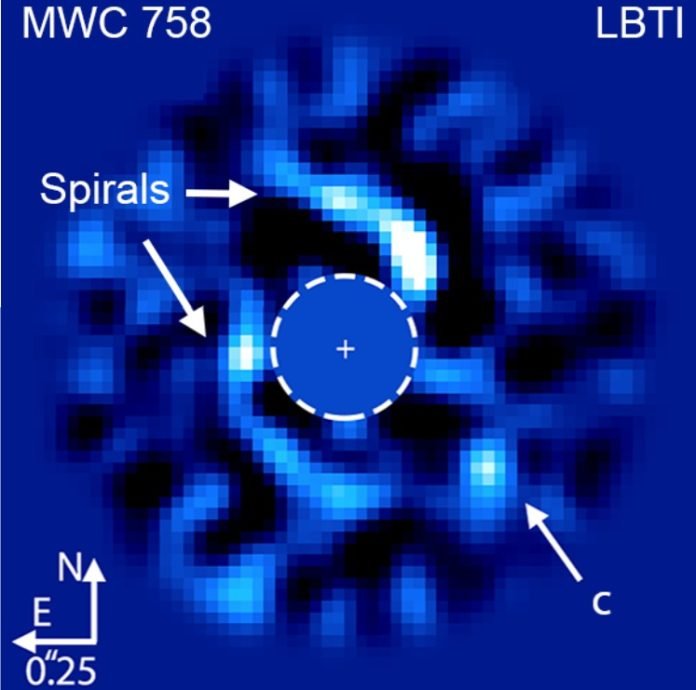

In a study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, astronomers from the University of Arizona announced the discovery of a huge exoplanet, named MWC 758c, that seems to be the artist behind the spirals in its home system.

They also suggested reasons why finding this planet had been so tricky in the past and how their methods might help reveal other hidden planets.

“Through our research, we now have a good piece of evidence suggesting that these spiral arms are the work of giant planets,” said Kevin Wagner, the lead author of the paper and a researcher at the UArizona Steward Observatory.

He also shared his excitement about the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, which will allow scientists to look for more planets like MWC 758c.

MWC 758c is part of a star system about 500 light-years away from Earth, and its star is just a few million years old – quite young compared to our 4.6 billion-year-old Sun!

This system still has a protoplanetary disk, as it takes about 10 million years for the spinning debris around the star to turn into planets, moons, asteroids, comets, or get ejected out of the system.

Around one-third of the 30 known protoplanetary disks show spiral arms – the beautiful swirls within the dust and gas of the disk. Observing these spiral arms gives us insight into the process of planet formation.

“Spiral arms can tell us a lot about how planets are born,” said Wagner. “The existence of this new planet further strengthens the idea that giant planets are formed early, gather mass from their surroundings, and then gravitationally influence the area where other smaller planets might form.”

However, the question remained: If a giant planet was causing these spirals, why hadn’t we spotted one until now?

Wagner and his team were finally able to find MWC 758c using the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer, or LBTI. This powerful telescope has an infrared camera similar to NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope and could detect the planet because it emits longer, redder wavelengths of light.

Despite being at least twice as big as Jupiter, MWC 758c had managed to remain hidden because of its unusually red color, making it the “reddest” planet ever discovered.

The team has come up with two theories about why the planet appears brighter at longer wavelengths. One possibility is that the planet is still hot from its formation and surrounded by dust.

Or, it could be a colder planet emitting most of its light at longer wavelengths. If the dust theory is correct, it suggests the planet might still be forming and could be in the process of creating its own moon system. If the planet is colder, scientists may need to rethink their understanding of how planets form.

“Either way, we now know we need to look for more ‘reddish’ baby planets in these spiral arm systems,” Wagner added.

The team is looking forward to observing the giant exoplanet with the James Webb Space Telescope in early 2024 to figure out which of the two theories is correct.

This could help us predict where other hidden planets might be found and what we should look for to detect them.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.