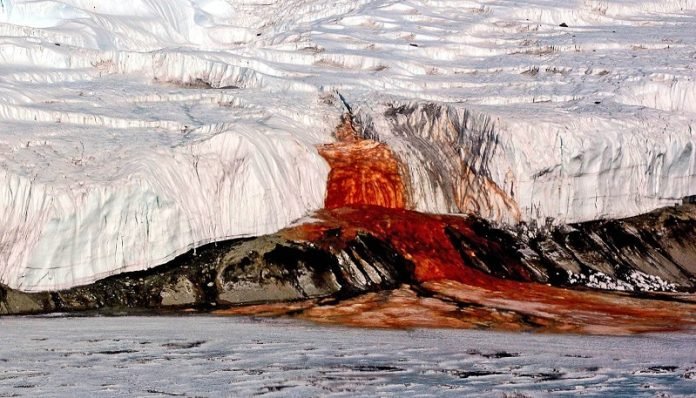

Have you ever heard of a waterfall that looks like it’s flowing with blood?

Over a century ago, British geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor came across this chilling sight in Antarctica.

The waterfall, located at the base of what’s now known as Taylor Glacier, became known as “Blood Falls.”

The water gushes out from beneath the glacier’s icy tongue, starting off clear but then rapidly turning into a startling red.

This strange spectacle has puzzled scientists for generations. That is, until now.

Enter Ken Livi, a research scientist at Johns Hopkins University. Using an ultra-powerful microscope at the university’s Materials Characterization and Processing facility, Livi took a deep dive into samples of the “bloody” water.

What he found were heaps of tiny, iron-rich spheres, known as nanospheres. These nanospheres, each about 100 times smaller than a human red blood cell, react with oxygen to turn the water a gory red.

Looking at the microscope images, Livi discovered that these nanospheres contained not just iron but other elements like silicon, calcium, aluminum, and sodium.

He was part of a group of scientists from various institutions who worked together on this research, which was published in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

One reason why this mystery took so long to solve is that previous researchers thought some kind of mineral was responsible for turning the water red.

But as Livi pointed out, minerals are made up of atoms arranged in a particular, crystal-like structure. These nanospheres don’t have that structure, which is why earlier methods failed to detect them.

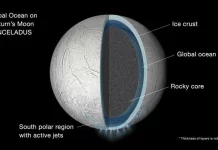

Livi also brought up another fascinating aspect: to truly grasp the enigma of Blood Falls, you have to consider Antarctic microbiology. Under the salty waters of the Antarctic glacier, there are ancient bacteria that could have been around for millions of years.

These bacteria inhabit the iron- and salt-rich waters beneath the glacier, providing an environment that might help scientists understand potential life on other planets with similar harsh conditions.

This was precisely why Livi, an expert in planetary materials, became involved in the Blood Falls project. He was interested in studying the samples from Blood Falls as if they were from a Martian landing site.

“What would happen if a Mars Rover landed in Antarctica? Would it be able to determine what was causing the Blood Falls to be red?” Livi asked.

Working with Jill A. Mikucki, a microbiologist who had previously studied Blood Falls, Livi examined the samples and found the nanospheres.

But Livi also acknowledged that their discovery raised another important point: the limitations of our current methods in analyzing materials on other planets’ surfaces.

Livi explains that Mars rovers might not have the capability to detect these tiny, non-crystalline nanospheres, especially on colder planets like Mars. To do so would require a transmission electron microscope, a device that we’re currently not able to send to Mars.

So, while the mystery of Blood Falls may be solved, it has shed light on another intriguing scientific challenge.

As we push forward in exploring other planets, we’ll need to improve our methods to truly understand the complex, and often microscopic, wonders that lie in our universe.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.