Ever wondered what happens when you hit an asteroid?

Thanks to NASA and the Hubble Space Telescope, we’re getting a front-row seat to the space version of a rock concert.

This cosmic spectacle is unfolding at asteroid Dimorphos, following NASA’s exciting DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) experiment last year.

In September 2022, NASA intentionally shot the DART spacecraft into Dimorphos at an incredible speed of 14,000 miles per hour.

This experiment aimed to change the asteroid’s course slightly as it orbits the larger asteroid Didymos. And it seems the DART experiment has had some rocking results!

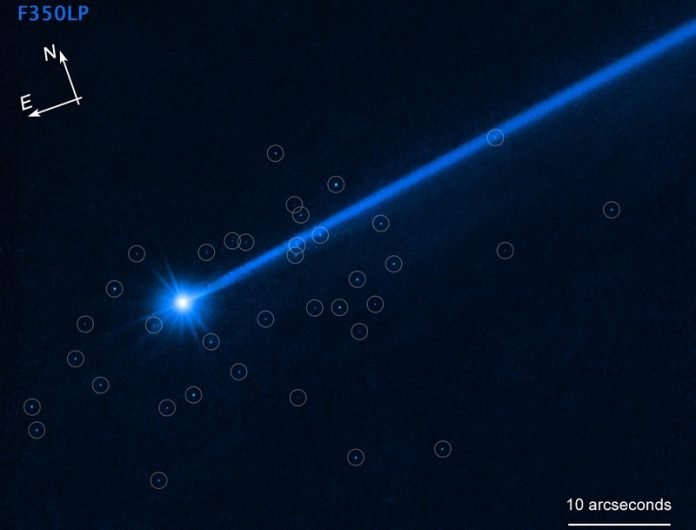

Hubble’s powerful vision has revealed a group of boulders, likely shaken off Dimorphos by the DART impact.

These space rocks, between three feet and 22 feet across, are slowly drifting away from the asteroid at a pace similar to a tortoise’s walk. They account for around 0.1% of Dimorphos’s mass.

David Jewitt, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, commented on the extraordinary observation: “We see a cloud of boulders carrying mass and energy away from the impact target.”

These results give us a peek into what occurs when an asteroid gets hit and material starts to be ejected.

This discovery will also influence the upcoming Hera mission by the European Space Agency. Hera, set to reach the binary asteroid in late 2026, will thoroughly study the aftermath of the DART impact. Jewitt added, “The boulder cloud will still be dispersing when Hera arrives.”

The sighted boulders are not likely fragments of Dimorphos shattered by the DART impact. They were already on the asteroid’s surface, as seen in a photo captured by DART just moments before collision. Jewitt estimates that the DART impact shook off about two percent of the asteroid’s surface boulders.

In an interesting twist, these observations might also help estimate the size of the crater left by DART on Dimorphos. Jewitt suggested the boulders could have been excavated from an area around 160 feet across, roughly the width of a football field.

Dimorphos is considered a flying rubble pile, likely formed from debris shed by its parent body, Didymos. So, it’s not fully clear how the boulders were ejected. They might be part of an ejecta plume seen by Hubble, or perhaps they were shaken loose by seismic waves from the DART impact, much like ringing a bell.

By tracking the boulders in future Hubble observations, we can better understand their trajectories and launch directions. With such fascinating findings, this cosmic rock concert is only just getting started!

The Hubble Space Telescope, a joint project between NASA and ESA, is managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and its science operations are conducted by the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.