Imagine the magic of witnessing the birth of a planet!

Thanks to the European Southern Observatory’s powerful telescopes, we are now a step closer to understanding how giant planets, like Jupiter, are born.

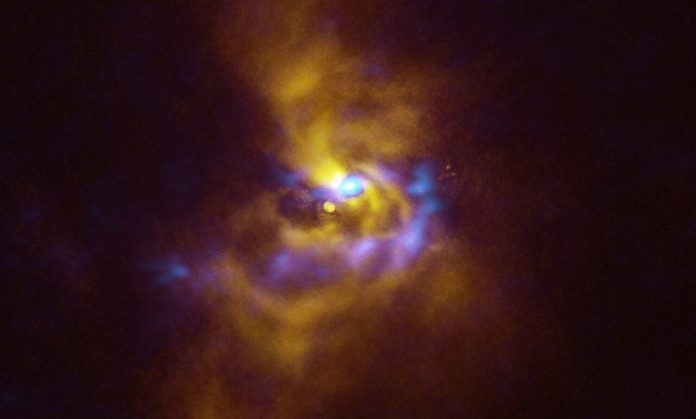

A stunning new image, released by the observatory, shows large lumps of dust, which could collapse and form huge planets, near a young star.

“This discovery is super exciting because it’s the first time we’ve spotted these large clumps around a young star that could become giant planets,” says Alice Zurlo, a researcher at the Universidad Diego Portales in Chile, who was part of the team making the observations.

The findings were published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The beautiful picture was taken using an instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) called SPHERE.

It shows the details of the material surrounding a young star named V960 Mon. This star, located more than 5000 light-years away in the constellation Monoceros, grabbed scientists’ attention in 2014 when it suddenly became over twenty times brighter.

The SPHERE image taken after this brightness surge showed that the material around V960 Mon is clumping together in a spiral shape, spanning distances larger than our entire solar system.

The researchers then decided to look at past observations of the same star system made using another telescope called ALMA, in which ESO is a partner.

The VLT image shows the surface of the dust around the star, while ALMA can see deeper into its structure. “With ALMA, it was clear that the spiral arms are breaking up and forming clumps that are as heavy as planets,” Zurlo explains.

Scientists think that giant planets can be formed in two ways. The first way is “core accretion,” where dust particles stick together.

The second way is “gravitational instability,” where big chunks of the material around a star shrink and collapse. While the first method has been backed by evidence before, the second method hasn’t had much support.

“This is the first time anyone has actually seen gravitational instability happening on a scale that could create planets,” says Philipp Weber, a researcher at the University of Santiago in Chile, who led the study.

The research team has been hunting for signs of how planets are formed for over a decade. “We couldn’t be happier about this amazing discovery,” says Sebastián Pérez from the University of Santiago, Chile, who was part of the team.

ESO’s instruments will continue to help scientists uncover more details about this intriguing planetary system in the making. ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), currently being built in Chile’s Atacama Desert, will play a significant role. It will be able to see the system in even greater detail, collecting crucial information about it.

“The ELT will allow us to explore the chemical makeup of these clumps. It will help us understand more about what the material from which potential planets are forming is made of,” Weber concludes.

Follow us on Twitter for more articles about this topic.