Most of us have heard about kidney stones and the pain they can cause, but not everyone knows exactly what they are, why some people get them, and how they are treated.

A kidney stone can form when minerals build up in the urinary tract, creating crystals that consolidate into a pebble-like mass.

A kidney stone may be small and unnoticeable. But in some cases, it can grow to the size of a pea and become trapped in the ureter (the tube that drains urine from your kidneys down to your bladder), blocking urine flow and causing serious pain.

In the worst cases, the pain is severe enough to prompt a trip to the emergency room, sometimes resulting in surgery.

One in 10 people will develop kidney stones at some point in their lives, and the number of cases has been gradually rising.

Although kidney stones are more common in men than in women, anyone at any age can develop one.

Piruz Motamedinia, MD, a urologist and kidney stone specialist, says the rise in kidney stone diagnoses has mirrored increases in cases of obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

While kidney stones are very treatable, “the vast majority of patients don’t know they have a kidney stone until they have symptoms, such as pain or bloody urine,” says Dr. Motamedinia.

“So, if you start noticing any symptoms, talk to your primary care physician right away.”

Below, Dr. Motamedinia answered some common kidney stone questions.

How do kidney stones form?

Kidney stones are essentially small “rocks” made of minerals, such as calcium, and other ingredients that accumulate within the urinary tract.

Urine normally filters out excess salts, minerals, and waste products resulting from the metabolic processes of building proteins and breaking them down within the body, he explains.

But when there is too much waste and not enough liquid to dilute it, crystals can develop and combine with other elements to form a stone.

“That’s why drinking enough water and having a high urine output is so important,” he says.

“If you dilute your urine by drinking water or almost any other fluid, you are less likely to form a crystal or a stone. If your urine is dark yellow or orange, that’s a sign you are dehydrated and need more fluids.”

Are there different kinds of kidney stones?

Yes. There are four main types of kidney stones:

Calcium stones, which include two subtypes: calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate stones. Calcium stones, especially calcium oxalate stones, are by far the most common type of kidney stone.

Oxalate is a natural substance found in many foods, including spinach, beets, almonds, and soy products. When there is too much waste in the body and too little liquid to flush it out, it can combine with the calcium in the urine to form stones.

The calcium phosphate stone is what it sounds like—it combines calcium with phosphate, an electrolyte (or electrically charged mineral).

While most people get more phosphate than they need from their diet, some of these stones are related to renal tubular acidosis, a metabolic condition that results when the kidneys aren’t performing their function of removing acids from the blood into the urine.

Uric acid stones can form when there is too much acid in the urine, which can result from eating too much fish, shellfish, poultry, pork, and meat (especially liver and other organ meats), which have high levels of purines, a common natural chemical compound.

Too many purines can cause uric acid in the kidneys to crystallize and harden. Drinking enough water, cutting down on high-purine foods, and maintaining a healthy diet, in general, can help with avoiding uric acid stones.

Struvite stones (also known as “infection stones”) are associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Bacteria from the infection produces ammonia, which makes the urine more alkaline, leading to the formation of struvite—a combination of ammonium, magnesium, and phosphate.

Struvite stones can form suddenly and quickly grow too large to pass. Surgery is often necessary to remove them.

Cystine stones. A rare, inherited disease called cystinuria causes an amino acid (cysteine) to leak from the kidneys to the urine, where it may cause stones to form.

Cystinuria is a lifelong condition and most people with it have recurring stones, so it’s especially important for them to drink enough water, follow a recommended diet, and, in some cases, take medication to control the level of cysteine in their urine to prevent stones from forming.

If a large stone forms, it may require surgical treatment.

How can you prevent kidney stones?

While each type of kidney stone is unique, there are recommendations that can help prevent any kind of kidney stone. The main one is hydration.

Dr. Motamedinia recommends drinking eight to 10 glasses (about 64 to 80 ounces) of water a day. That can include coffee, tea, and juice but not dark cola drinks.

While the reasons for avoiding dark cola are not completely clear, colas contain phosphoric acid, which is known to acidify urine and can help create certain kinds of kidney stones, Dr. Motamedinia explains.

Instead, he suggests filling a measured container with water every morning and drinking it throughout the day “with specific goals in mind to achieve proper hydration.”

A healthy diet can also help, and studies show the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet can reduce the risk of kidney stones.

The DASH diet promotes vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, as well as limits full-fat dairy products, tropical oils, and fatty meats, which are more acidic.

Because calcium can block other substances in the digestive tract that cause stones, it helps to include calcium-rich foods in your diet, such as milk, cheese, yogurt, and leafy greens.

It’s also best to avoid excess salt, which can pull calcium out of the body and into the urine. If you are lactose intolerant, calcium-fortified soy and oat milk are good substitutes, he adds.

In terms of daily calcium, the recommended dietary calcium allowance for adults is 1,000 to 1,200 milligrams, depending on a person’s age and sex. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) provides a chart for all age groups.

For salt intake, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends less than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day.

One strategy for reducing sodium intake is to read the labels on packaged and prepared foods, which often contain a surprising amount of salt, to help make sure you’re staying within the recommended amount.

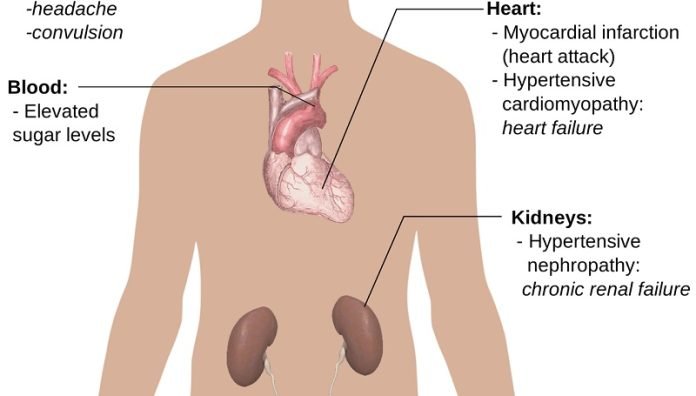

It may also help to know that certain conditions, including gout, obesity, and diabetes mellitus (a disease characterized by inadequate control of blood glucose levels—it includes type 1, type 2, gestational, and other types of diabetes), can put you at a higher risk for kidney stones.

This is also true for certain medications, including diuretics and calcium-based antacids.

Another risk factor is a family history of kidney stones.

“We’re studying whether people with a family history have a genetic risk factor or if it’s because people in certain families follow a similar diet that puts them at risk,” Dr. Motamedinia says.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Many kidney stones are diagnosed when a person has symptoms, such as bloody urine, nausea and vomiting, pain, and an urgent need to urinate.

They may go to the emergency room after a stone has become stuck at some point in its journey through the body, causing irritation, a backup of urine, and intense pain.

“The passage of the stone, along with the blockage and swelling of the kidney, is what causes the pain; the stretching of the organ can result in severe pain and nausea,” he says.

“The pain can also come and go in waves as the ureter contracts to push the kidney stone through.”

If a kidney stone is suspected, a CT scan or ultrasound can confirm it—a CT scan will also provide information on the size and shape of the stone.

Doctors can analyze the stones for their content, providing clues about the cause, which can be helpful in preventing future stones. Kidney stone recurrence is not uncommon; rates may be as high as 50% within five to seven years.

Not everyone with a kidney stone needs a specialist, but you may need a urologist if a stone is large or in a difficult location, or if there are multiple or recurring stones.

- How are kidney stones treated?

The proper treatment for your kidney stone will depend on a range of factors, including its make-up, size, location, and the amount of pain you are experiencing. Below are four treatment approaches:

Wait for the stone to pass. If the stone is small, it may pass without your experiencing any pain or knowing you had it.

If you already know you have a stone—either because it was diagnosed after you reported symptoms or it was identified during imaging for another condition—a doctor can use imaging to measure it and determine how far it has moved along the urinary tract.

“There are people who pass large stones without an issue, and there are people who have a really hard time passing smaller ones; it depends on the person’s anatomy and pain tolerance,” Dr. Motamedinia says.

Taking over-the-counter pain medication as recommended and, occasionally, prescription medications that can dilate the urinary tract help to manage the pain and facilitate the passing of the stone, adds Dr. Motamedinia. “As always, maintaining hydration is imperative,” he says.

Shockwave lithotripsy. This is a common, noninvasive kidney stone treatment that uses a machine to administer sound wave energy from outside the body to crush the stone into pieces that can be passed.

“Choosing the right stone and the right patient are important. A stone that is too large or too hard is not ideal.

And, in certain cases, the patient’s size, if they are pregnant, or if they use blood thinners may indicate the need for an alternative treatment,” says Dr. Motamedinia. “However, in many cases, shockwave lithotripsy works quite well.”

Ureteroscopy. This is an endoscopic approach and the most commonly used method to remove kidney stones. A small, flexible camera is inserted into the urinary tract, where it is used to visualize the stone.

The stone is broken into manageable pieces with a laser, and pieces are retrieved using a tiny basket—or they are turned into a fine powder that can be passed easily.

The procedure can take 20 minutes to an hour and a half, depending on the size and location of the stone, among other factors.

“The considerations mentioned above that would preclude the use of shockwave lithotripsy are less of a concern for ureteroscopy, making it a more versatile option,” says Dr. Motamedinia.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Used for large stones unsuitable for other treatment options, this is a minimally invasive surgery performed through an incision in the back for direct access to the kidney.

Instruments are inserted and used to pulverize the stone and suck it out. The procedure can take three hours.

Every kidney stone is different, Dr. Motamedinia explains. “Not all information will apply to every patient. Many of the restrictive diets you might see online, for instance, aren’t backed up by evidence and usually don’t apply to most patients,” he says.

“When in doubt, consult a urologist, even if it’s just to make sure you’re doing the right thing.”

Written by Kathy Katella.

If you care about kidney health, please read studies about how to protect your kidneys from diabetes, and drinking coffee could help reduce risk of kidney injury.

For more information about kidney health, please see recent studies about foods that may prevent recurrence of kidney stones, and eating nuts linked to lower risk of chronic kidney disease and death.