Scientists at MIT have made a fascinating discovery about a new “tidal disruption event” (TDE) that happened close to Earth.

This event occurs when a supermassive black hole rips apart a passing star, which causes a burst of radiation that can be detected by telescopes on Earth and in space.

A TDE is a rare event that happens once every 10,000 years or so, and it can be detected by the burst of light that arrives at telescopes.

Most of the light from a TDE comes from X-rays and optical radiation, but this new event was shining brightly in infrared, which is a different type of light.

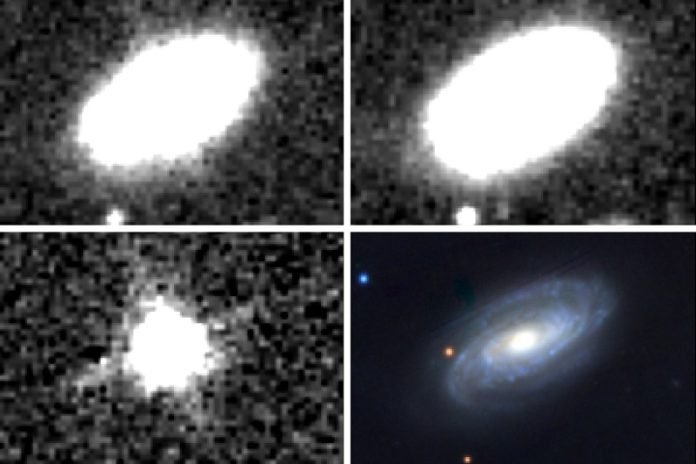

The new TDE was discovered in a galaxy called NGC 7392, which is about 137 million light-years from Earth. This is actually quite close in astronomical terms and is one-fourth the size of the next-closest TDE.

The scientists believe that there are many more TDEs like this one that have been missed because traditional methods of detecting them only look for X-rays and optical radiation, which can be obscured by dust.

The team of researchers discovered the new TDE while they were looking for general transient sources in observational data. They used a special search tool to look for potential transient events in data taken by a space telescope called NEOWISE, which has been scanning the entire sky since 2010 at infrared wavelengths.

They discovered a bright flash that appeared in the sky near the end of 2014. They traced the flash to a galaxy that was 42 megarparsecs from Earth and finally determined that it was most likely a TDE, and the closest one observed so far.

The scientists also discovered that the galaxy where the TDE arose was actively producing new stars.

This is important because star-forming galaxies produce a lot of dust, which can obscure any X-ray or UV radiation that would otherwise be picked up by optical telescopes. This could explain why astronomers have not detected TDEs in star-forming galaxies using conventional optical methods.

The team suggests that searching in the infrared band could reveal many more, previously hidden TDEs in active, star-forming galaxies.

“Finding this nearby TDE means that, statistically, there must be a large population of these events that traditional methods were blind to,” says Christos Panagiotou, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

The new discovery has important implications for our understanding of black holes and their host galaxies. Black holes are fascinating objects that have puzzled scientists for decades. They are so massive that they warp space-time around them, and nothing can escape their gravitational pull, not even light.

Scientists believe that every galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center. These black holes are thought to play an important role in the evolution of galaxies, but there is still much that we don’t understand about them.

The new discovery suggests that there could be many more TDEs in star-forming galaxies than we previously thought. This is important because TDEs can tell us a lot about the properties of black holes and the galaxies they reside in.

The scientists believe that searching for TDEs in the infrared band could be a game-changer for our understanding of black holes and their host galaxies.

They suggest that we should try to find these events in infrared if we want a complete picture of black holes and their host galaxies.

In conclusion, the new discovery of a TDE in a nearby galaxy is an exciting development for astronomers. It shows that there could be many more TDEs in star-forming galaxies than we previously thought, and that searching for them in the infrared band could reveal many more previously hidden events.

The discovery of TDEs is an important step towards understanding the properties of black holes

Written by Jennifer Chu.