On August 17, 2017, around 70 telescopes collectively turned their gaze to a fiery collision between two dead stars that took place millions of light-years away.

The telescopes watched the event unfold in a rainbow of wavelengths, from radio waves to visible light to the highest-energy gamma rays.

As the pair of ultra-dense neutron stars crashed into each other, they flung debris outward that glowed for days, weeks, and months.

Some of the onlooking telescopes spotted gold, platinum, and uranium in the searing blast, confirming that most heavy elements in our universe are forged in this type of cosmic collision.

Were that the end of the story, this cosmic event would have been remarkable in itself, but three other detectors were present for astronomical gathering that day—two belonging to the National Science Foundation-funded LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) and one belonging to Europe’s Virgo.

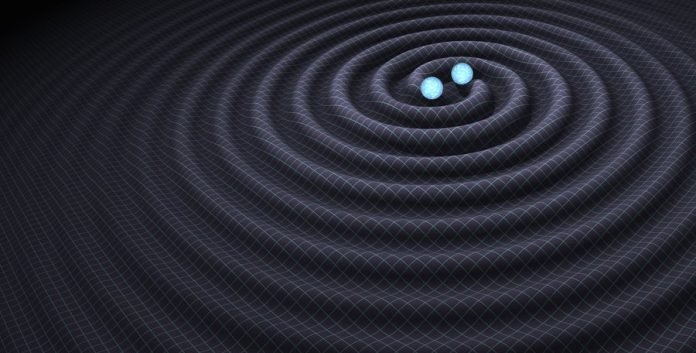

LIGO and Virgo observe not light waves but gravitational waves, or shivers in space and time produced by massive accelerating objects.

As neutron stars spiral together, they generate gravitational waves before they merge and explode with light.

It was the LIGO–Virgo gravitational-wave network that alerted the dozens of telescopes around the world that something astonishing was taking place in the skies above. Without LIGO and Virgo, August 17, 2017, would have been a typical day in astronomy.

Since that time, the LIGO–Virgo network has detected only one other neutron star merger; in that case, which occurred in 2019, light-based telescopes were not able to observe the event. (LIGO-Virgo has also detected dozens of binary black hole mergers, but those are not expected to produce light in most instances.)

With LIGO–Virgo scheduled to turn back on this May, astronomers are excitedly preparing for more explosive neutron star mergers. One pressing question on the minds of some LIGO team members is: Can they detect these events sooner—perhaps even before the dead stars collide?

To that end, the researchers are developing early-warning software to alert astronomers to neutron star mergers up to seconds or even a full minute before the impact.

“It’s a race against time,” says Ryan Magee, a Caltech postdoctoral scholar who is co-leading the development of early-warning software along with Surabhi Sachdev (MS ’17, PhD ’19), a professor at Georgia Tech. “We are missing precious time to understand what happens before and right after these mergers,” he says.

Eleven hours later, the source is found

Once LIGO detects a likely neutron star collision, the race begins for telescopes on the ground and in space to follow up and pinpoint its location.

The LIGO–Virgo network, which consists of three gravitational-wave detectors, helps narrow in on the approximate location where the fireworks are happening while light-based telescopes are required to identify the exact galaxy in which the neutron stars reside.

For the August 17 event, known as GW170817, most of the light-based telescopes were not able to start searching for the source of the gravitational-wave event until nine hours later.

The LIGO–Virgo team sent its first alert to the astronomical community 40 minutes after the neutron star collision and the first sky maps, outlining the event’s rough location, 4.5 hours after the event.

But by that time, the region of interest in the southern skies had dipped below the horizon and out of view of the southern telescopes capable of seeing it.

Astronomers would have to anxiously wait until nine hours after the event to begin combing the skies.

By about 11 hours after the neutron star collision, several ground-based optical telescopes had at last pinned down the location of the source of the waves: a galaxy called NGC 4993, which lies about 130 million light-years away.

Gearing up for the next run

With 11 hours missing from the story of how neutron stars slam into each other and seed the universe with heavy elements, astronomers are eagerly awaiting more neutron star smashups.

For LIGO–Virgo’s upcoming run, which will also include observations made by Japan’s KAGRA, the detectors have been undergoing a series of upgrades to make them even better at catching gravitational-wave events and thus neutron star mergers.

The team expects to detect four to 10 neutron star mergers in next run and as many as 100 in the fifth observing run of the current advanced detector network, planned to begin in 2027. Future runs with more advanced detectors are planned for the 2030s.

One new feature to be employed at the next run is the early-warning alert system. The specialized software will complement the main software that has been routinely used to detect all the gravitational-wave events so far.

The main software, also called a search pipeline, looks for weak gravitational-wave signals buried in noisy LIGO data by matching the data to a library of known signals, or waveforms, that represent different types of events, such as black hole and neutron star mergers.

If a match is found and confirmed, an alert is sent to the astronomical community. The early-warning software works in the same way but uses only truncated versions of the waveforms so that it can work faster.

“The detectors are constantly taking new data in an observing run, and we are comparing our waveforms to the data as they come in. If we use truncated waveforms, we don’t have to wait for as much data to be collected to do our comparison,” Magee says.

“The trade-off is that the signal needs to be loud enough to be detected using truncated waveforms. It’s important to still run the main pipelines alongside the early-warning pipeline to pick up the weaker signals and get the best final localizations.” Magee, Sachdev, and their colleagues are working on an early-warning pipeline called GSTLAL; additional early-warning pipelines for LIGO–Virgo are also in the works.

Before the fireworks

As neutron stars spiral around each other like a pair of ice dancers, they orbit faster and faster and give off gravitational waves of increasingly higher frequencies.

The final dance between neutron stars lasts longer than those between black holes, up to several minutes in the frequency bands LIGO is most sensitive to, and this gives LIGO and Virgo more time to catch the lead-up to the stars’ dramatic finale.

In the case of GW170817, the pair of mingling neutron stars spent six minutes at the frequency ranges detectable by LIGO–Virgo before the two bodies ultimately coalesced.

The LIGO early-warning software’s truncated waveforms are designed to catch snippets of this last dance; in fact, the researchers think the software will eventually catch a neutron star merger up to one minute before the collision.

If so, that will give telescopes around the world more time to find and study the explosions.

“In the next run, we might be able to catch one of the neutron star mergers 10 seconds ahead of time,” says Sachdev. “By the fifth run, we believe we can catch one with a full minute of warning.”

For astronomers, one minute is a lot of time. Caltech professor of astronomy Gregg Hallinan, the director of Caltech’s Owens Valley Radio Observatory, says that early warnings of imminent neutron star mergers will be particularly important for gamma-ray, X-ray, and radio telescopes because the collisions may burst at these wavelengths right at the very start.

“Radio telescope arrays like the Long Wavelength Array at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory (OVRO-LWA) and Caltech’s future 2,000-antenna Deep Synoptic Array (DSA-2000) might be able to detect a radio flash that is theorized to occur at the time the neutron stars merge and in some models during the final inspiral before the merger,” says Hallinan.

“That will teach us about the immediate environments of these massively destructive events. What’s more, seeing a radio flash could also help us quickly pin down the location of the mergers.”

Shreya Anand, a Caltech graduate student, says that early optical and ultraviolet observations of the mergers can reveal new information about their evolution, such as how elements are formed in the fast-moving material ejected from the collisions.

“Our algorithms figure out how to best cover different patches of sky and for how long to ensure the maximum chance of finding the target,” she says.

“We are missing interesting physics in the early phases of the mergers. The early-warning software from the LIGO team and the software for our telescope searches will speed up our chances of finding an event early. This will ultimately give us a more complete picture of what is going on.”

The early-warning study led by Magee appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The study led by Sachdev also appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Written by Whitney Clavin