Astronomers have discovered the closest black hole to Earth, the first unambiguous detection of a dormant stellar-mass black hole in the Milky Way.

Its close proximity to Earth, a mere 1,600 light-years away, offers an intriguing target of study to advance understanding of the evolution of binary systems.

The U.S. National Science Foundation provided funding support for the work.

The astronomers used the Gemini North Telescope on Hawaii, operated by NSF’s NOIRLab, one of the twin telescopes of the International Gemini Observatory.

The discovery was made possible by making observations of the motion of the black hole’s companion, a sunlike star that orbits the black hole at about the same distance as the Earth orbits the sun.

Though there are likely millions of stellar-mass black holes in the Milky Way galaxy, those few that have been detected were uncovered by their energetic interactions with a companion star.

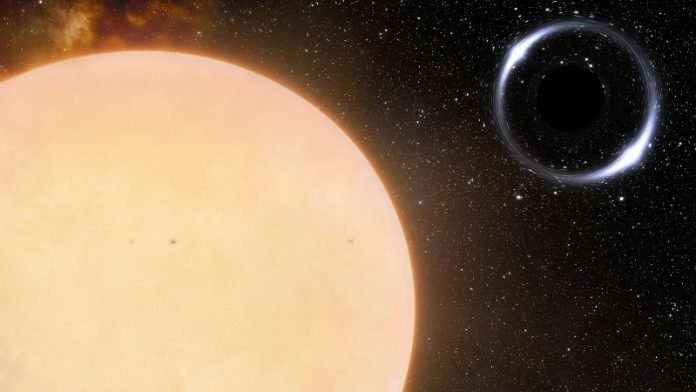

As material from a nearby star spirals in toward the black hole, it becomes superheated and generates powerful X-rays and jets of material.

If a black hole is not actively feeding, it is dormant and not directly detectable.

This dormant black hole is about 10 times more massive than the sun and is located about 1,600 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, making it three times closer to Earth than the previous record holder.

“Take the solar system, put a black hole where the sun is, and the sun where the Earth is, and you get this system,” explained Kareem El-Badry, an astrophysicist and lead author of a paper published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The team relied not only on Gemini North’s superb observational capabilities but also on Gemini’s ability to provide data on a tight deadline, as the team had only a short window in which to perform their follow-up observations.

“As part of a network of space- and ground-based observatories, Gemini North has not only provided strong evidence for the nearest black hole to date but also the first pristine black hole system, uncluttered by the usual hot gas interacting with the black hole,” said NSF Gemini Program Officer Martin Still.

The International Gemini Observatory is operated by a partnership of six countries: Canada, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Korea, and the United States through NSF. The University of Hawaii manages the Gemini North site.