For the past two centuries, humans have relied on fossil fuels for concentrated energy; hundreds of millions of years of photosynthesis packed into a convenient, energy-dense substance.

But that supply is finite, and fossil fuel consumption has a tremendous negative impact on Earth’s climate.

“The biggest challenge many people don’t realize is that even nature has no solution for the amount of energy we use,” said University of Chicago chemist Wenbin Lin.

Not even photosynthesis is that good, he said: “We will have to do better than nature, and that’s scary.”

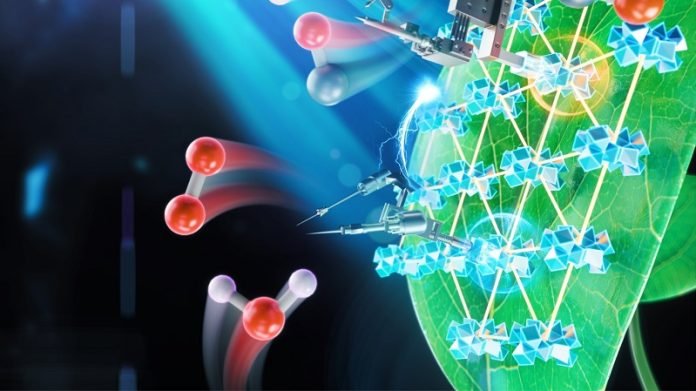

One possible option scientists are exploring is “artificial photosynthesis”—reworking a plant’s system to make our own kinds of fuels.

However, the chemical equipment in a single leaf is incredibly complex, and not so easy to turn to our own purposes.

A Nature Catalysis study from six chemists at the University of Chicago shows an innovative new system for artificial photosynthesis that is more productive than previous artificial systems by an order of magnitude.

Unlike regular photosynthesis, which produces carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water, artificial photosynthesis could produce ethanol, methane, or other fuels.

Though it has a long way to go before it can become a way for you to fuel your car every day, the method gives scientists a new direction to explore—and may be useful in the shorter term for production of other chemicals.

“This is a huge improvement on existing systems, but just as importantly, we were able to lay out a very clear understanding of how this artificial system works at the molecular level, which has not been accomplished before,” said Lin, who is the James Franck Professor of Chemistry at the University of Chicago and senior author of the study.

‘We will need something else’

“Without natural photosynthesis, we would not be here. It made the oxygen we breathe on Earth and it makes the food we eat,” said Lin. “But it will never be efficient enough to supply fuel for us to drive cars; so we will need something else.”

The trouble is that photosynthesis is built to create carbohydrates, which are great for fueling us, but not our cars, which need much more concentrated energy. So researchers looking to create alternates to fossil fuels have to re-engineer the process to create more energy-dense fuels, such as ethanol or methane.

In nature, photosynthesis is performed by several very complex assemblies of proteins and pigments.

They take in water and carbon dioxide, break the molecules apart, and rearrange the atoms to make carbohydrates—a long string of hydrogen-oxygen-carbon compounds.

Scientists, however, need to rework the reactions to instead produce a different arrangement with just hydrogen surrounding a juicy carbon core—CH4, also known as methane.

This re-engineering is much trickier than it sounds; people have been tinkering with it for decades, trying to get closer to the efficiency of nature.

Lin and his lab team thought that they might try adding something that artificial photosynthesis systems to date haven’t included: amino acids.

The team started with a type of material called a metal-organic framework or MOF, a class of compounds made up of metal ions held together by an organic linking molecules.

Then they designed the MOFs as a single layer, in order to provide the maximum surface area for chemical reactions, and submerged everything in a solution that included a cobalt compound to ferry electrons around. Finally, they added amino acids to the MOFs, and experimented to find out which worked best.

They were able to make improvements to both halves of the reaction: the process that breaks apart water and the one that adds electrons and protons to carbon dioxide. In both cases, the amino acids helped the reaction go more efficiently.

Even with the significantly improved performance, however, artificial photosynthesis has a long way to go before it can produce enough fuel to be relevant for widespread use.

“Where we are now, it would need to scale up by many orders of magnitude to make an sufficient amount of methane for our consumption,” Lin said.

The breakthrough could also be applied widely to other chemical reactions; you need to make a lot of fuel for it to have an impact, but much smaller quantities of some molecules, such as the starting materials to make pharmaceutical drugs and nylons, among others, could be very useful.

“So many of these fundamental processes are the same,” said Lin. “If you develop good chemistries, they can be plugged into many systems.”

The scientists used resources at the Advanced Photon Source, a synchrotron located at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, to characterize the materials.

Written by Louise Lerner.