The unpredictability of polycystic ovary syndrome never surprises Samantha Schon, M.D., a reproductive endocrinologist and infertility specialist with the University of Michigan Health Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital.

While imbalanced hormones are the root cause of a laundry list of typical symptoms – irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, insulin resistance and excess body hair – PCOS presents differently in every person.

It’s a symptom puzzle and health care providers seek help in putting each piece together.

The best ally to do that – to get the proper diagnosis and early treatment – is the patient themselves.

Approximately 10% of women of reproductive age across the United States have PCOS, but medical experts believe that figure is much higher with many cases undiagnosed.

To better understand PCOS, Schon shares the condition’s nuances here to empower people to report seemingly unrelated health issues or symptoms to their physician, which will lead to better health and accurate diagnoses.

7 things to know about PCOS

What is PCOS?

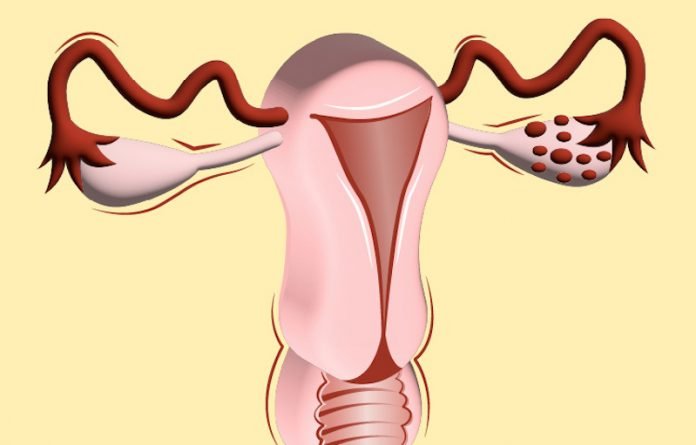

PCOS is a metabolic disorder, marked by an overabundance of male sex hormones, where women tend to have a lot of eggs in their ovaries, and yet they’re not released regularly.

“In our clinic, it’s one of the most common causes of infertility in women,” Schon said. “But not everyone with PCOS has infertility.”

Many symptoms overlap or indicate other conditions, so people often don’t realize they have PCOS until they struggle to get pregnant and discover infertility.

PCOS is a lifelong condition that may lead to future long-term health risks. It’s commonly connected to uterine cancer, heart problems, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, Type 2 diabetes, obesity, sleep apnea, anxiety or depression.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that more than half of those with PCOS develop Type 2 diabetes by age 40. That’s why early knowledge about it is critical, Schon said.

What are PCOS symptoms?

This is the tricky part: PCOS is a heterogeneous disease, meaning its symptoms vary from person to person. They can begin as early as adolescence and continue after menopause. All women, regardless of size, shape, or weight, may get PCOS.

The most common symptoms are:

- Irregular periods, typically nine or fewer a year

- Elevated levels of male hormones (androgens)

- Obesity

- Weight gain or the inability to lose weight

- Moderate to severe acne

- Unwanted male-like hair growth on face, chest, abdomen or back (hirsutism)

- Insulin resistance

- Enlarged ovaries that contain follicles

Other symptoms, though less common, include:

- Male-patterned balding or thinning hair

- Unexplained fatigue

- Dark, velvety skin patches (acanthosis nigricans)

- Skin tags

What causes PCOS?

The cause remains unknown, but researchers continue to see correlations between genetic and environmental factors.

The syndrome does run in families, but because it’s impacted by behavioral and environmental conditions, scientists point out a family’s lifestyle choices may impact the condition rather than genetics.

How is PCOS diagnosed?

Unfortunately, no single test exists to determine if you have polycystic ovary syndrome. This disease requires a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning a physician rules out other conditions that can cause the symptoms, like irregular menstruation.

An underactive thyroid, for instance, or elevations in other brain hormones like prolactin, might slow the frequency of a period.

To qualify for the diagnosis of PCOS, a patient must have two out of following three criteria, Schon explains. They are:

- Irregular periods

- Lab results or clinical signs of excess male hormones (androgens)

- Polycystic ovaries, which aren’t cysts at all, but rather follicles in a fluid-like sack that surround the eggs

What tests help diagnose PCOS?

In order to diagnose the condition, Schon says health care providers typically gather a medical history, do a physical exam, draw bloods tests to measure hormone levels, and order an internal ultrasound to scan the reproductive organs, including the ovaries.

What’s the treatment for PCOS?

Treatment has changed significantly since PCOS was first described in 1935.

A combination of lifestyle changes and often medication is usually the first-line treatment.

For those trying to avoid pregnancy, birth control pills are the go-to treatment. “They cause the liver to increase something called sex hormone binding globulin, which is a protein that can soak up those excess androgens,” said Schon.

Birth control pills also protect the uterus by ensuring that the uterus sees an important hormone called progesterone.

Those with irregular cycles tend to develop a thick lining in the uterus, which can increase the chances of uterine cancer, she said.

For those trying to get pregnant, physicians typically prescribe a medication, like letrozole to stimulate ovulation and the subsequent release of an egg.

Lifestyle interventions, including losing weight, exercising, and eating foods that lesson insulin resistance, may also help PCOS patients.

“A small percentage of weight loss, about 5–10%, can be enough sometimes to help them resume more normal periods,” she said.

Another question she often receives is about diet. No diet is better than another to help PCOS. “I typically say the best diet is the one that a patient can stick to,” she said.

When Schon was learning about treatments during her fellowship, she learned about historical treatments of PCOS that included surgery.

“They performed ovarian wedge resections or ovarian drilling, where they would go in and surgically take out a portion of women’s ovaries out or burn holes in their ovaries to cause them to ovulate.

At least now we have great medications to help the release of eggs,” she said.

Medications also address the other symptoms that emerge with PCOS, including insulin resistance, excess hair growth and acne.

Is PCOS curable?

Polycystic ovary syndrome is treatable, but not yet curable.

“When you read the literature, there are studies that show that significant weight loss can basically cure PCOS,” Schon said.

“I don’t think you ever totally cure it because it’s still a metabolic disorder at its core. With weight management, you can control it, but it isn’t necessarily something that’s curable, at least at this time.”

Written by Rene Wisely.

If you care about health, please read studies about how often women should have bone tests, and Estrogen hormone may protect women from severe COVID-19.

For more information about health, please see recent studies about diet that could boost healthy aging in women, and results showing antibiotics used in midlife linked to cognitive decline in women.